- accueil >

- TIES >

- Pouvoirs de l'image, affects et émotions >

- Reconfigurations imaginaires : la guerre entre émo ... >

Reconfigurations imaginaires : la guerre entre émotions collectives et traumatismes individuels

The Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) and the Emotional Rhetoric of Anti-British Postcards

Abstract

How can one measure the impact of images on affects and collective emotions? The postcard, a new medium located at the crossroads of propaganda, mass consumption, and modernity that emerged in the 19th century, provides an interesting perspective on the issue. This article will focus more particularly on the anti-British cartoon postcards published during the Anglo-Boer War. Cultural allusions, references to the animal world, scatological jokes, as well as gallows humour were part of the strategies deployed by cartoonists to manipulate public opinion and create strong group feelings, thus turning what might be regarded as mere humorous images into a devastating political weapon.

Plan

Texte intégral

1Among the numerous and remarkable means of communication that marked the second half of the Victorian era was the picture postcard. Not only did it come as a natural consequence of the progress made in illustrations (photography, engravings), but it also transformed the lives of many Victorians living both in Britain and in the colonies. As the Victorian era witnessed many important changes which transformed it into the foremost consumer society of the time, so did the technical devices produced by the industrial revolution propel the British into modernity. The picture postcard, like other new technological devices, made an emotional impact on the population: “Emotions were not confined to individuals but were shared collectively across a whole network of connections—including technological ones” (Malin 187).

2Though the postcard became a means of cohesion within the British Empire, it is within the German Empire, around 1865, that the idea of a “post-card” is said to have emerged. The idea did not however gain currency immediately. A few years later, a specimen of a postcard was presented by Dr Emmanuel Hermann to the Austrian postal authorities, and in October 1869, the first official postcard was published in Vienna. The following year, the production of postcards began in France and England. From 1894 onwards, private publishers could sell their own cards, leading to millions of postcards being exchanged across the world by the end of the century. The postcard evolved quickly from then onwards both in size and contents. From a mere 120 x 78 mm, the postcard increased to 140 x 90 mm. The picture was originally a lithograph, later to be replaced by a photograph, showing the evolution in the techniques of illustration. These pieces of cardboard became extremely popular throughout the world.

3Naturally, propaganda got hold of this little item. Sheryl T. Ross defines it as “(1) an epistemically defective message (2) used with the intention to persuade (3) a socially significant group of people (4) on behalf of a political institution, organization, or cause […]” (Ross 29). The postcard was not only an easy way to communicate but it was also a handy collectible which multiplied the opportunities to display the message conveyed by the postcard to a large audience. Further, as pointed out by Ross: “the development of various mass media, […] allowed access to an ever-increasing audience for mass persuasion,” (Ross 17) thus turning images into what Mondzain, in her turn, would describe as “an instrument of power over bodies and minds” (Mondzain 22). In the late 19th century, the danger of images was perceived as being linked to a lack of education:

Political caricatures were viewed as especially dangerous because their impact was seen as greater and more immediate than that of the printed word and because, while large segments of the especially feared “dark masses” were illiterate and thus not susceptible to subversive words, anyone could understand the meaning of a drawing. (Goldstein np)

4The effectiveness of images can therefore be accounted for as linked to the emotions they provoke, and consequently, to the viewer’s reaction: “Understanding emotions can provide understanding and meaning to what moves people to one action over another, one belief over another, and one vision of life, themselves, or other” (Smith 95-96).

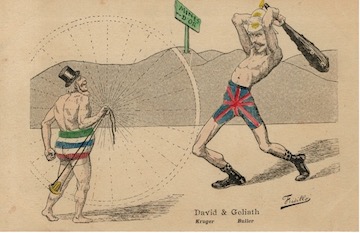

5Emotions are complex things, and they explain many social phenomena, and particularly one, among many, which is central to our study, that of modern communications. At the turn of the 19th and 20th century, the picture postcard became a media, since any kind of event could be photographed and turned into a postcard. Its immediate sale and distribution barely a few days after the event occurred (sometimes the same day) indeed made it a “media.” The Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) which was fought in South Africa, was a war of propaganda, particularly when continental Anglophobia raged and reached its peak. Debunking British imperialism was on the agenda of French, German and Dutch artists. Their Anglophobia was revealed on postcards. Collecting anti-British postcards, displaying them in albums and sharing the pleasure of viewing them with visitors became part of a social ritual that strengthened a sense of belonging to a community. Propaganda reached further heights as major strides were made in the techniques of photography and cinema and printing equipment, with better quality books, newspapers, and magazines. Images thus became even more important weapons with a network of anti-British postcards spreading across the world. Paul Kruger, the president of the Transvaal, one of the two Boer republics, engaged against the Crown. He is represented as the not-yet King David, confronting British General Goliath-Buller in a French cartoon [Figure 1].

[Figure 1] Fredillo. “David (Kruger) & Goliath (Buller)”. Unknown editor, no date. The sign at the back points toward “gold mines”. French postcard from a series of six from the same artist whose real name is lost.

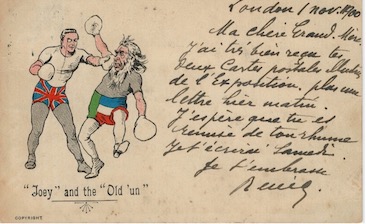

6Needless to say, Britain of course had her own counter-offensive with a production of postcards which poured ridicule on the Boers, and more particularly on Paul Kruger, with simple, easy to understand messages [Figure 2].

[Figure 2] Unknown artist. “‘Joey’ and the ‘Old ’un’” [Joseph Chamberlain fighting Paul Kruger]. Unknown editor, no date. British postcard.

7Therefore “[a]side from the fact that the impact of drawings was seen as more immediate than that of the printed word and more accessible to the illiterate, caricatures were also seen as more threatening than words because they were perceived as more visceral and therefore more powerful” (Goldstein np). Drawing on Baudrillard’s approach to seduction and his system of objects, as well as on other specialists of media and emotion studies, this article tries to understand the mechanisms of viewers’ emotions when facing a postcard, and examines the strategies set up by artists and propagandists to produce in the viewer an emotion which will ultimately lead him to side with the artist.

The spectator’s gaze at the heart of the postcard craze

8In a globalized context, social psychology shows that the individual is submitted to the group and its gaze: “Self is not only evaluated by direct ‘Me’ reflections from the looking glass created by others’ responses to our behavior; self is also evaluated by reference to the moral yardstick contained in the generalized other” (Turner 480). In other words, we are conditioned and constrained by the group we feel we belong to. This group is artificially strengthened by propaganda: “the senders of propaganda often aim at creating an ‘us’ against ‘them’ mentality” (Ross 20). Such evidence is reinforced by crowd psychology (a branch of social psychology), as demonstrated through the SIDE model (Social Identity of Deindividuation Effects model). SIDE argues that individuals become anonymous components of groups, that they feel secure within the group and can thus behave in a way they would not as individuals (Vilanova). In the case of the Anglo-Boer war, French Anglophobia stemmed from the imperial competition between the two countries. One is reminded here of René Girard’s concept of “mimetic desire” (when a group or a person desires what the other has) as being at the root of violence. In a similar vein, social psychologists refer to a “game metaphor” between two groups in conflict, not because they are different, but because they share common beliefs, aspirations, and values: “It is because we want the same thing – but can’t all have it – that we fight others for the commonly desired prize” (Elcheroth and Reicher 13).

9Cartoon postcards, which bring up programmed emotional reactions against a given person or group, are at the core of reception studies. They play a vital role in research on the impact of emotional responses triggered by provocative propaganda tools such as, in our case, picture postcards. The reception of postcards is another, more complicated area of cartophilia or the study of postcards (or deltiology as it is sometimes referred to). The difficulty lies in extracting testimony from addressees of postcards. What was their understanding of the message conveyed on the postcard? Did they share the same view as the sender? Did they have the same references and the same connotations? Were they, on the contrary, brought to align themselves with the sender? For a researcher to make assumptions and draw conclusions would imply a good knowledge of the context, the period, and the people’s reaction to similar cartoons. The success of postcards (attested by the underground “pirate” reproductions of cartoons) suggests they were highly valued: people wanted to preserve postcards, giving them added value, making them best-sellers and collector’s items.

10Moreover, emotions are deeply linked to our freedom of thought. This article will therefore attempt to understand the power of images in relation to laughter and mockery, such as in the case of British imperialists who were ridiculed or reproved, portrayed as “uncivilized beings.” A number of scholarly studies, which this chapter will draw from, analyse individual emotions which are embedded in those of a group. According to the “intergroup emotions theory or IET” (Sasley 453), “we can and should theorize more rigorously about how groups in international relations can be said to experience emotions and then take action according to these emotional reactions and provide a theoretical justification for doing so” (Sasley 452-453). Poking fun at someone also develops cohesion: the laughing group shares the very values that the lampooned persons lack (or so they think). Cartoons, therefore, and more generally the pervasion of images through new media, have a significant part to play. Indeed, satirists and caricaturists first and foremost express a political opinion through their art, and the war in South Africa between Boers and Britons was a powerful ideological battlefield:

Blatant propaganda is inherent in war art and can be found in abundance in the Anglo-Boer War material. It may well be that the complex ideologies underlying the War lent themselves to easy distortion, but whatever the cause, the symbolism contained in propaganda rewards detailed study. It exhibits a wealth of innuendo and exaggeration which tells later generations much about the mechanisms of contemporary propaganda and what appealed to segments of late nineteenth century society. (Carruthers 16)

11Attacking the representations and the emotions of those targeted by propaganda is part and parcel of what satirical images are meant for. These images are powerful weapons against an enemy, as “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Some artists of the time became very efficient in the activity and their art was seen as a strong weapon. Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956), for example, was a Dutch painter and cartoonist “whose drawings helped shape views of gas and the war in general, was said to be ‘worth at least two army corps to the Allies’” (Russell 32).

12Propaganda is therefore at the heart of the process. Pascal Molinier argues that propaganda is meant to strengthen the cohesion of the audience through a sense of belonging that leads it to action. He adds that the source of the propaganda must adopt a position of authority so that propaganda becomes a source of conflict, the best way to create group cohesion and give it an enemy (Molinier 22). This is when images have a role to play, as they justify the action (or should we say the reaction) to what is seen as offensive. As images are produced by humans, they are linked to human social relations and “they therefore require a wider frame of analysis in their understanding, a reading of the external narrative that goes beyond the visual text itself.” (Banks & Zeitlyn 13) Emotions are a strong and influential means of action: an offended person can go as far as to challenge his or her opponent to obtain reparation for the offence. Images provoke emotions to trigger an expected response.

13At the turn of the 20th century, the potential enemy or rival for several European countries was Britain and her Empire. This is because France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany were also leading imperialists. Others like Russia with interests in Afghanistan and India had geo-political reasons to see Britain stumble. The Fashoda incident in 1898, for instance, was seen in France as a humiliating defeat although no blood was shed. “Perfidious Albion” as Great Britain was then nicknamed in France, was blamed for its hegemonic position in a colonial context. In the face of the biggest fleet and the most powerful army in the world, not to mention a certain amount of jingoism, Europe produced a strong feeling of Anglophobia which rapidly spread to most Western countries. Artistic activity bloomed and participated in the general appreciation of the situation. Satirical representations published in newspapers or on postcards tried to increase the already strong anti-British feeling through irony and satire, or on the contrary through the description of the evillest aspects of humankind.

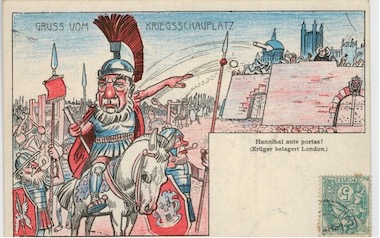

“[K]illing them with laughter”: a typology of Anglo-Boer war postcard propaganda

14The themes and targets of these artists were Queen Victoria, Edward Prince of Wales, Cecil Rhodes, John Bull, Lord Roberts, Lord Kitchener and the simple British soldier nicknamed Tommy Atkins. Postcards sometimes carried witty messages accompanying the pictures based on well-known references. The Bible is an example: Paul Kruger (President of the Transvaal) was compared to David and General Buller (Commander in Chief of the British forces in South Africa) to Goliath [see Figure 1]. Artists also made historical references, when Kruger was described as Hannibal besieging Rome (London) [Figure 3].

[Figure 3] Unknown artist. “GRUSS VOM KRIEGSSCHAUPLATZ. Hannibal ante Portas! (Krüger belagert London.)”. Unknown editor, no date. German edition of the French postcard series “Théâtre de la Guerre”.

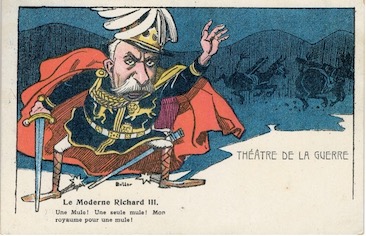

15Sometimes the postcards addressed educated people who had a good knowledge of William Shakespeare: the “Theatre of war” series portrays General Buller who suffered unexpected major setbacks facing the Boers during the first months of the war [Figure 4].

[Figure 4] Unknown artist. “Théâtre de la guerre. Le Moderne Richard III. Une Mule! Une seule mule! Mon royaume pour une mule!”. Unknown editor, no date. French postcard.

16He is depicted as “The modern Richard III” who required “a mule! Just one mule! My kingdom for a mule.” This is a distorted quote from Shakespeare’s famous historical play when the king cries out for a horse and not a mule. The desperate General Buller, just like King Richard III, sees the horrific situation he is in as he reaches his hand out, in a vain theatrical gesture, to stop the British army mules bearing military equipment from absconding to the enemy as they did during the conflict on 30 October 1899 at the Battle of Nicholson’s Neck, near Ladysmith. They had taken with them most of the water supplies, ammunition, artillery and all hopes of British Lieutenant-Colonel Frank Carlton to be able to defeat the Boers.

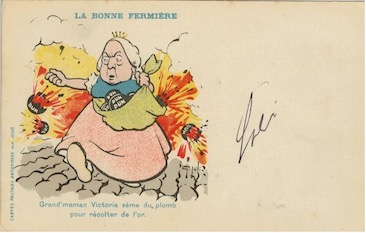

17Sometimes artists went even further by making puns; in a French postcard, Tommy Atkins declares: “The Queen has no need to send me more chocolate, I get prunes every day.” In early 20th century French slang, a “prune” meant a bullet or a cannon ball. Or when, in two instances, a Boer is verbally aggressive towards a British soldier who has burnt Boer farms and is being told to shut up: “La ferme” means both “the farm” (French) and “shut up” (French slang). Most of the time, the simple picture was enough to create laughter or disgust. The Queen was often portrayed as an old lady who was afraid of what was happening in South Africa or whose only concern was to get her hands on the gold and diamond mines of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. In another French cartoon (the good farmer), we see her walking through a field scattering bombs, with the caption: “Granny Victoria sows lead to harvest gold.” [Figure 5].

[Figure 5] G. Julio. “LA BONNE FERMIERE. Grand’maman Victoria sème du plomb pour récolter de l’or. ” “Cartes postales artistiques par Julio.” Unknown editor, no date.

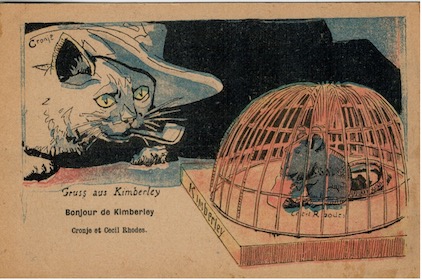

18French or Belgian postcard (there is a Dutch and German version of this postcard and the rest of the series). The illustration was first published in La Réforme (15 October 1899), a Brussels weekly. Sometimes the postcard was a fable in which animals spoke. The British lion is often stung by the Boer bee, gored by the Boer bull or vainly trying to eat porcupine Kruger. We also find the big Boer cat which is about to eat the mouse Rhodes trapped in a cage called Kimberley, as a reference to the besieging of the “diamond capital” by the Boers (14 October 1899 – 15 February 1900) alongside Ladysmith and Mafeking [Figure 6].

[Figure 6] Unknown artist. “Gruss aus Kimberley. Bonjour de Kimberley. Cronje et Cecil Rhodes”. Unknown editor, no date.

19Turning a real event into a symbolic fable was a favourite French punning device. French pupils had and have, for many decades, been educated through the Fables of Jean de la Fontaine which, although politically minded, have a moral undertone. They were, and still are considered fit to enlighten generations of young French pupils and teach them good moral values such as “More haste, less speed” (from the fable of the tortoise and the hare, inspired by Aesop). Telling a story was thus the objective of the cartoons reproduced on the postcards. They were meant to be clear, immediately comprehensible, with a good pun. They likewise could be shared with other people.

20Fables which swap animals for humans are an old human tradition, since they protect the artist from being prosecuted because he can say “this is just a fable” and deny the fact that these animals really represent humans. This is what we find in the “Roman de Renard” (12th century) or the “droleries” (funny things), which are to be found in “drolerie (funny) margins” (part of the “decorated margin” genre) in 13th and 14th century illuminated manuscripts and meant to give a lighter side to the text. Sometimes these “droleries” mock priests and monks and even the Pope, by associating them with animals, including hybrid creatures. One such drolerie is the Pope depicted as an ass, an image taken up during the Reformation by Lucas Cranach with his pope-donkey (Papstesel).

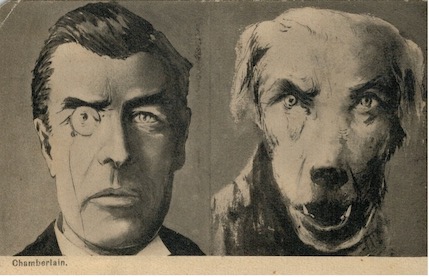

21In the same way, during the conflict in South Africa, Joseph Chamberlain was compared to a dog, which is a way to denounce his “animal” or “beast-like” behaviour towards the Boers [Figure 7].

[Figure 7] Unknown artist. “Chamberlain”. Unknown editor, no date. French postcard.

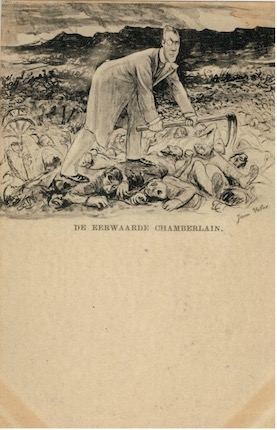

22Chamberlain was one of the favourite targets of continental artists, who (rightly) saw him as the promotor of the war in South Africa. French artist Jean Veber portrays him on a postcard dressed as a gentleman, ploughing Boer bodies to harvest gold [Figure 8].

[Figure 8] Veber, Jean. “DE EERWAARDE CHAMBERLAIN”. Unknown editor, no date. Illustration from the French satirical newspaper l’Assiette au Beurre, special issue “Les camps de reconcentration au Transvaal”, 28 Sept 1901, or its German edition “Das Blutbuch von Transvaal” (Pub. Dr Eysler & Co). Dutch postcard.

23What the postcard conveys in terms of emotions is the comforting satisfaction of distinguishing, without any doubt, the right from the wrong; people who laugh at someone always think they are virtuous and that the punned “victims” deserve what they get.

24A certain evolution in postcard themes can be noticed throughout the conflict. In the first months of the war, European artists had plenty of material to poke fun at Tommy Atkins as the British suffered numerous defeats (Black Week, 10-17 Dec. 1899). The battles of Colenso, Spion Kop, Stormberg and later Vaalkrantz made British soldiers easy targets. One may well imagine how ludicrous it was to see an overwhelming number of professional soldiers overrun by small commandos of farmers of the guerrilla-fighter type. These farmers could even go as far as to besiege the “soldiers of the Queen” in British towns in South Africa: namely Mafeking, Kimberley and Ladysmith. Hence many postcards depicted a beautiful young woman called Lady Smith going away hand in hand with a Boer, waving goodbye to a crying John Bull (Teulié). Thus, there was a lighter side to the representations of the war, as denouncing it was meant to ridicule British troops, officers (Sir Redvers Buller, Lord Kitchener), and leaders (Queen Victoria, Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Salisbury).

25Yet, gently joking about the British troops or leaders was not enough. More emotions were triggered off over the course of the conflict. Representing an erection, copulation or defecating and urinating was not tolerated in European representations, neither by the public, nor the cartoonists, nor the medias (Ronge 183). As W. J. T. Mitchell explains, “[e]xcrement, garbage, genitals, corpses, monsters, and the like are often regarded as intrinsically disgusting or objectionable”; these objects, however, elicit great interest when they are deliberately mediated in front of a spectator: “[t]his is the moment when objectionable (or inoffensive) objects are transfigured by depiction, reproduction, and inscription, by being raised up, staged, framed for display” (Mitchell 125). While some people in England were not affected by such fierce lampooning, it nevertheless brought on some vivid reactions, from time to time. A few cartoons were so insulting to the Royal Family and the government that Queen Victoria decided to cancel her annual spring holiday in Southern France and the Prince of Wales refused to go to the opening of the Great Exhibition in Paris in 1900. Anglo-French relations had always been strained and the bawdy scatological themes used by French cartoonists were understandably considered offensive. In that sense, a cartoon by C. de Amara [Figure 9] also became famous.

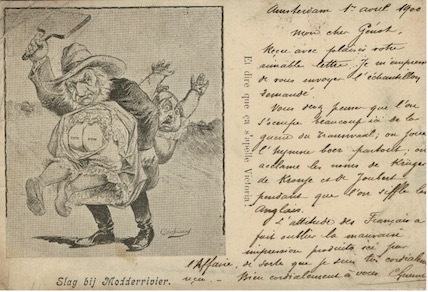

[Figure 9] Da Amaral C. “Slag bij Modderrivier” & “Et dire que ça s’appelle Victoria!”. Uit. Ludwig, Damrak Amst. No date. Illustration captioned “English Correction” (in English) from the French satirical newspaper La Caricature, 25 Nov. 1899. Dutch postcard.

26It depicts Paul Kruger holding Queen Victoria under his left arm and spanking her bare backside on which one can read “dum dum,” a reference to the expanding bullets forbidden by the Hague Peace International Convention in 1899, but which British troops were accused of using in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War. This cartoon appeared in the French satirical magazine La Caricature on 25 November 1899 under the title “English Correction” (Greenwall 85). A Dutch editor used it on a postcard to celebrate a Boer victory over the British at the battle of the Modder River on 28 November 1899. The double offence that was felt by British citizens who viewed that type of postcard was, first and foremost, that body nudity had been a Christian taboo since the end of the Middle Ages; people walking about naked were thus seen as shameful people who had to go through social sanctions (Ronge 183) just as the “savage” was despised because his nudity was seen as a token of his backwardness and primitivism. The Renaissance polemicists used nudity to debunk people whom they considered unfit for their charge, by exposing the naked truth about them. Secondly, showing a representation of an intimate part of the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland and Empress of India, the “Mother of the People” could be seen as a crime of lèse-majesté, particularly as it showed her to be in the position of a child that had to be scolded and punished by a patriarchal figure. For the pro-Boer viewers of the postcard, the funny side prevailed as it was a form of catharsis that transposed the viewers’ fantasies into reality (albeit virtual): wishing the Queen to be punished. What is more, the image of a caring and loving woman is desecrated, as she is thus associated with war atrocities which she seems to accept and support.

27Scatological cards meant to amuse the public and be aggressive towards the targeted people (the British) were therefore not uncommon during the Anglo-Boer War, and especially on the part of French artists. One postcard, by Charles O. Denizard (Orens) [Figure 10], was published by editor M.Y. Paris.

[Figure 10] Denizard, Charles O. (Orens). “Une Tempête sur un crâne” V.H. [Victor Hugo] Les Misérables. MY Paris, no date. French Postcard.

28The caption “Une Tempête sur un crâne” (“a tempest on a skull”) plays with the title of a chapter by Victor Hugo in his masterpiece Les Misérables (1862). The real quote is “Une tempête sous un crane” (“a tempest in a skull”). It expresses the turmoil experienced by the novel’s hero Jean Valjean, who is faced with a difficult choice: either to reveal his real identity as a former convict and save an innocent man, or to remain silent and continue his cosy life as mayor of Montreux-sur-Mer, thus avoiding going back to prison. Regrets and shame are part of what the distorted quote in the caption of the postcard is about but flatulence and defecation make it deeply offensive; four Boers are “forcing” the names of British defeats into the head of Edward VII either by hammering his skull, defecating on it or breaking wind.

29In the bawdy tradition of French Renaissance author François Rabelais, parody and satire use scatology to debunk people (Ducini “Chier” 64). It is an old mode of mocking people, which goes back at least to the Latin poet Horace; the latter had recourse to mockery in his Satires VII (Saturae) in which the god Priapus scares two witches by releasing a wind (Ducini “le pet” 206). One could also mention the “Roman de Renard” (12th century) in which a bear falls on his rear and passes wind, provoking laughter around him. As for defecation, it is often even more aggressive for it devaluates the opponent and is charged with contempt. Seeing the names of Boer victories over the British in South Africa forced into the king’s skull – Tugela (Dec 1899), Magersfontein (11 Dec 1899) Spion Kop (23-24 Jan 1900) and Tweefontein (25 Dec 1901) – leads the French viewer to understand, thanks to the reference to Victor Hugo, that Edward VII should be ashamed of himself, and have regrets about what has been done by the Crown in South Africa. Laughter through a shocking process is undoubtedly the emotion that Orens wants to provoke. He was such a famous artist at the turn of the 20th century that the Shah of Iran ordered his portrait from him.

30Symbolically defecating or urinating on someone is part of the dehumanising process launched against someone. A dog urinating on a British leader is also to be found on an Anglo-Boer War postcard from France [Figure 11].

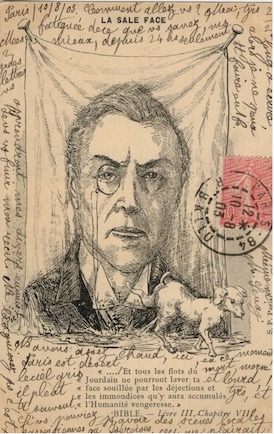

[Figure 11] Pick, M. “LA SALE FACE” “‘…Et tous les flots du Jourdain ne pourront laver ta face souillée par les déjections et les immondices qu’y aura accumulés l’Humanité vengeresse.’ BIBLE – Livre III, Chapitre VIII”. SP Paris, no date. French postcard.

31It is entitled in French “The dirty face.” It shows Joseph Chamberlain’s huge portrait on a white cloth, hanging on a wall. The secretary of State for the colonies is easily recognisable thanks to his monocle. The caption, a pseudo-Biblical quote, gives added value to the card as it seems to justify the offending image; humanity (and presumably God) is against Chamberlain and what he does to the Boers. Things went so badly between the two nations that some people talked about fighting. Fortunately, things settled down, as can be seen in an article published in the French daily paper Le Petit Journal on 17 December 1899:

It seems we will not have a war with England because of cartoons, and that the battleships of both nations will not engage each other just because some French Journalists fancied publishing irreverent caricatures about the ruler of the kingdom [Queen Victoria] whom Mr Chamberlain took on an adventure that the whole world condemns. (Levrai 402, my translation)

Collective emotions as a political weapon

32About the British satirical press, we can say that cartoons give us some clues about British collective emotions at the turn of the 20th century. Indeed, cartoonists induce or extrapolate the adhesion or hostility of their readership according to the enthusiasm or reproval likely to be produced by such or such event (Millat 15). It is a fact that cartoons target emotions, even if some are meant to be witty and to appeal to the intellect of the viewer. Most of them aim at being understood by the greatest number of customers possible, to become fashionable and consequently bestsellers. Thus, as stated by Jean Baudrillard,

[w]e shall not, therefore, be concerning ourselves with objects as defined by their functions or by the categories into which they might be subdivided for analytic purposes, but instead with the processes whereby people relate to them and with the systems of human behaviour and relationships that result therefrom. (Baudrillard 4)

33Stirring up passions and therefore emotions is what caricatures and cartoons are about. They can lead offended people to sue those who had mocked them, such as artist Aristide Delannoy who was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment for having represented French General Albert d’Amade as a butcher during a campaign in Morocco in 1908. Others were assassinated as in the case of the murder by Islamist radicals of the French staff of satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in 2015 for having published cartoons of Islam prophet Muhammad. Cartoons and caricatures can thus trigger strong emotions and consequently provoke powerful reactions: “Both neural scientists and psychologists have demonstrated that individual-level emotional reactions to stimuli tell us whether we are scared, excited, happy, fearful, hopeful, and so on – which then condition our specific responses” (Sasley 453).

34These examples show that cartoons are anything but innocent artwork and that if they are well advertised, they can reach a vast public and therefore influence a whole society. But it can also be argued that the viewer is very often a consenting person to the message. One of the foremost objectives of cartoons is to make people smile and laugh. It is a way to desacralise a person or a people. Dictators who promote a cult of their personality dread being mocked, as it destroys the (positive) image they have painstakingly elaborated through the display of pictures and statues on the territory they rule. Hence, during the Anglo-Boer War, metaphors of expulsed British soldiers being driven into the sea, as in this German postcard published in Leipzig, were numerous [Figure 12].

[Figure 12] A.F. (The artist is only known through his initials). “Der Boerenkrieg. n° 6069.” “Au weh! Das hatte ich mir anders vorgestellt.” Druck u Verlag. Bruno Bürger & Ottillie, lith. Anst. Leipzig, no date. German postcard.

35The astonished British soldier says, “O Dear! I had imagined it differently.” Besides the positive emotions of seeing British troops being kicked out of South Africa, German viewers would also appreciate the comment of the soldier who is puzzled that things did not go as planned. The fact that some Boers had a German ascendency (such as President Paul Kruger, or General Louis Botha), alongside some form of Anglophobia, accounted for German public opinion being pro-Boer. The underlying message is not to take things for granted but to beware of a small group of South African white farmers.

36Retreating British troops are also part of the cartoonists’ stock-in-trade, as is shown in the cartoon by German artist Arthur Thiele, with a bilingual caption in French “A ‘well organised’ British retreat, or the retrograde march” and, in Flemish, “A well-arranged return trip.” The pun is created by the visible contradiction between text and image which shows a chaotic British retreat [Figure 13].

[Figure 13] Thiele Arthur (German artist, Leipzig). “Une retraite ‘bien organisée’, ou la marche – rétrograde” “Eén goed geregelde terugtocht”. French and Dutch captions. Unknown editor, no date.

37Not surprisingly, the fiercest cartoonists against Britain at that time were the Netherlands, Germany and France, nations which supported the Boers who were descendants of Dutch, German, and French settlers.

38Colonial competition was not the only reason for continental Anglophobia. Sometimes puns became cynical, and what was meant to be funny became less so when death was evoked. This is what we see in a Dutch cartoon published in Amsterdam, showing British soldiers running away from Boer soldiers’ dead bodies, carrying away wallets from which paper money bills are coming out and watches presumably taken from the dead Boer soldiers, while a British soldier is holding a bleeding knife, which thus presents him not only as a looter but as a murderer as well [Figure 14].

[Figure 14] Unknown artist. “Groet uit Elandslaagte”. Uitg(ave) N.J. Boon Amst(erdam), no date. Dutch postcard.

39Representing British soldiers as plunderers is typical of anti-British propaganda against the war, but it also appeals to a Continental sense of belonging and strengthens that feeling. Indeed, while “the receivers of propaganda are possible supporters of that group or cause who may not be linked formally with each other,” (Ross 20) propaganda can help forge such links: “In targeting possible supporters of their cause, political groups are attempting to influence the beliefs, desires, opinions, and actions of the socially significant group of people” (Ross 20).

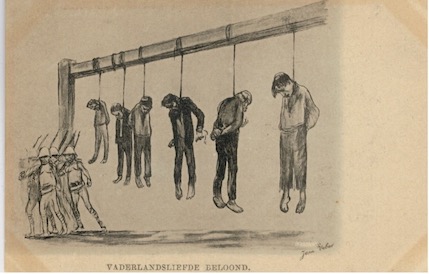

40The satirical representations of the second part of the Anglo-Boer War, which started with the taking of the capitals of the Boer Republics by British troops, Bloemfontein, and Pretoria, respectively on 13 May and 5 June 1900, were different. When Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener took command and began to launch successful attacks against the Boers, the themes on the postcards changed too. There were no more direct references to Boer victories (except small guerrilla ones, as the feat of Christiaan de Wet) but an increase in more bitter subjects, such as the behaviour of British soldiers depicted as murderers and thieves performing mass hangings [Figure 15], or hooligans kicking pregnant women in the stomach [Figure 16].

[Figure 15] Veber, Jean. “VADERLANDSLIEFDE BELOOND.” Unknown editor. No date. Illustration published in the French satirical newspaper L’Assiette au Beurre, special issue “Les camps de reconcentration au Transvaal”, 28 Sept 1901, or its German edition “Das Blutbuch von Transvaal” (Pub. Dr Eysler & Co). Dutch postcard.

[Figure 16] Veber, Jean. “ARME VROUWEN.” Unknown editor., no date. Illustration published in the French satirical newspaper L’Assiette au Beurre, special issue “Les camps de reconcentration au Transvaal”, 28 Sept 1901, or its German edition “Das Blutbuch von Transvaal” (Pub. Dr Eysler & Co). Dutch postcard.

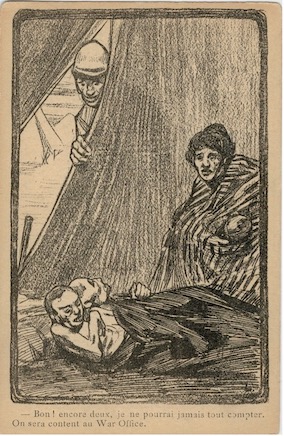

41The British “reconcentration” camps, in which thousands of Boer women and children died, became subjects for cartoons, and so succeeded in presenting England as a barbaric nation [Figure 17]. 1

[Figure 17] Artist known as “L” or Lenny. “ Bon! encore deux, je ne pourrai jamais tout compter. On sera content au War Office”. Unknown editor, no date. French postcard from a series of twelve cards.

42Disgust and repulsion are the emotions meant to be activated here. This is also what French artist Jean Veber (1868-1928), author of the two sketches mentioned in the previous paragraph [Figures 15 and 16], wanted to convey. There is no historical evidence, however, that mass hangings ever took place, and the emotional response Veber tried to elicit could therefore be described as “inappropriate”: “In order to capture the emotional component of some propaganda, we can say that some propaganda encourages inappropriate emotional responses. Birth of a Nation is designed to inspire hatred toward a race of people, false pride, and ignoble courage which are all examples of inappropriate emotional responses” (Ross 21).

43Having studied under Maillot, then under Delauney and Cabanel at the École des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris, Jean Veber began his career as a painter, before becoming a lithographer, an activity for which he was awarded several prizes. He turned to satire with the help of his brother who worked for the satirical journal Gil Blas. Jean Veber went on to contribute for many years to newspapers such as Le Rire, Gil Blas, Le Journal and L’Illustration (Greenwall 224). It is undoubtedly the fierceness of his representations which forged his reputation, their capacity to shock and provoke being a way to stand out. Starting from 1897, he had problems with the French authorities for a caricature targeting Otto von Bismarck, entitled “Boucherie” (butchery/slaughter), which depicted the Chancellor of the German Empire as a butcher by trade cutting people up as if they were mere beef meat. He did it again during the Anglo-Boer War with a famous satirical drawing entitled L’Impudique Albion (indecent Albion),2 which was displayed on the back cover of issue n° 26 of L’Assiette au Beurre, published on 28 September 1901, and entitled “Les camps de reconcentration au Transvaal” (reconcentration camps in the Transvaal)3 (Doizy).

-

4 The title of the cartoon published in the Se...

44The three Veber postcards under scrutiny are part of a sixteen-postcard series taken from the “reconcentration camps” issue (see figures 8, 15 and 16). They were published in France with a French caption by J. Picot from Paris, with a French and Dutch caption, or with a Dutch caption only. Just like figure 13 that bore French-Dutch captions, and if we consider cartoons as representative of the mood of the time, we understand that the pro-Boer side had more than one champion in Europe, with France and the Netherlands being closely followed by Germany. Some of Veber’s cartoons were considered too offensive and obscene to be reproduced on postcards. Examples include L’Impudique Albion, and also a cartoon of Edward VII inside a wine barrel wetting himself (a reference to his alleged drunkenness and interest in Parisian women when he was Prince of Wales)4 (Monico). However, it seems that “coloured pirated crude copies of L’Impudique Albion and L’Épave by unidentified artists and publishers exist” on postcards (Greenwall 224); if so, this would prove the magnitude of the success of the cartoons, considering that reproducing and secretly publishing postcards to make a profit are a token of success and that the strength of an image emanates from the desire to see it and have it (Mondzain 31).

45What remains certain is that the battle around the Impudique Albion censorship was indeed a battle for power (that of provoking politically orientated emotional responses): “Images, like all works of art, can be desecrated or deprived of their strength” (Mondzain 33). Indeed the French government complied with the British authorities and had the offensive cartoon veiled (King Edward VII face appeared on Britannia’s bear back-side). This, in turn, led to the postcard editor not publishing L’Impudique Albion on a postcard. But in doing so, the government involuntarily triggered a keen interest in the cartoon which resulted in its being sought after by buyers and collectors. It paved the way for it becoming an iconic representation of censorship centuries later, long after its original anti-British message had become obsolete.

Conclusion

46“The image awaits its visibility, which emerges from the relation established between those who produce it and those who look at it” (Mondzain 30). While it is true that the anti-British cartoons during the Anglo-Boer War were in the tradition of satirical drawings of previous centuries, continuing a lampooning genre unbound by time, this article has also demonstrated that the Anglo-Boer War had its own specificities. Propaganda-bearing postcards were part of a group construction of reactions to debunk Britain, as a potential imperial enemy. In other words, French, German or Dutch social identities during the Anglo-Boer War were constructed in reaction to “perfidious Albion,” portrayed not only as an arch-enemy to be overcome in order to ease imperial competition, but also as a scapegoat for all the negative demeanours and drawbacks of their own societies. The depersonalisation process that takes place when the individual consciously or unconsciously submits to the group to which he feels he belongs is one of the explanations for the anti-British feeling that arose during the war in South Africa. This pattern was enhanced by the picture postcard which, in targeting the group rather than the individual, became a new medium of propaganda, a new provider of emotions, alongside the emerging cinema.

47Just as today’s social media can be a means of harassing, mocking and eventually psychologically destroying someone, the postcard industry, along with the press of the beginning of the 20th century, was part of a “propaganda war” that opposed Europeans to the British who, because of “[t]he well-known sensitivity of the British to pictorial criticism of their Boer War policy,” (Goldstein np) objected to being lampooned. This sensitivity is easy to understand when people realize that visible and symbolic representations and emotions are two sides of the same coin that, when combined, constitute the key to power: “the one who is the master of the visible is the master of the world and organizes the control of the gaze” (Mondzain 20). Just as in 1899 the French journalist previously quoted wondered whether the two nations would go to war over cartoons, so we might wonder the same thing in 2021. Is not violence too high a price to pay for the defence of freedom of speech and the right to produce what are seen by some as offensive cartoons? On 21 October 2020, French President Macron tackled this issue during the funeral service of Samuel Paty, secondary school history teacher, murdered by an Islamic extremist for having used Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons in his class, as part of the national history programme. When Emmanuel Macron stated that the French people (with an inclusive “we”) would not give up cartoons, he was pleading the case for the right to lampoon for political reasons as a fundamental human right to the freedom of speech, even if that speech was offensive. The debate is ongoing but, whatever the outcome, it confirms that the power of images will remain linked to human emotions, for better or for worse.

Works cited

BANKS, Marcus and David ZEITLYN. Visual Methods in Social Research (2003). Los Angeles: Sage, 2015.

BAUDRILLARD, Jean. The System of Objects (1968). Trans. James Benedict. London, New York: Verso, 1996.

BURKE, Peter. Eyewitnessing. The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2019.

CARRUTHERS, Jane. “Introduction.” Artists & Illustrators of the Anglo-Boer War. Ed. Ryno Greenwall. Vlaeberg (South Africa): Fernwood Press, 1992. 11-16.

DUCINI, Hélène. “Chier, chieur”. Les procédés de déconstruction de l’adversaire. Ed. Bruno de Perthuis. Ridiculosa 8 (2001): 64. Brest: Presses de l’Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

DUCINI, Hélène. “Le pet foireux”. Les procédés de déconstruction de l’adversaire. Ed. Bruno de Perthuis. Ridiculosa 8 (2001): 206. Brest: Presses de l’Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

DOIZY, Guillaume. “L’Impudique Albion de Jean Veber: un dessin censuré?” Caricatures&Caricature, May 2015. http://www.caricaturesetcaricature.com/2015/05/l-impudique-albion-de-jean-veber-un-dessin-censure.html (Accessed 26 December 2020).

ELCHEROTH, Guy and Stephen REICHER. Identity, Violence and Power. Mobilising Hatred, Demobilising Dissent. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017.

GIRARD, René. Deceit, Desire, and the Novel. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1965.

GOLDSTEIN, Robert. “Political Caricature and international complications in Nineteenth Century Europe”. Michigan Academician 30, (March 1998): 107-122. Republished in Caricatures&Caricature. http://www.caricaturesetcaricature.com/article-10259459.html (Accessed 26 Dec. 2020).

GREENWALL, Ryno. Artists & Illustrators of the Anglo-Boer War. Vlaeberg (South Africa): Fernwood Press, 1992.

LEVRAI, Simon. « La semaine ». Supplément illustré du Petit Journal (17 décembre 1899): 402. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k7163609/f2.item.zoom (Accessed 8 July 2021)

MALIN, Brenton J. “Media, Messages, and Emotions.” Doing Emotions History. Eds Matt Susan J. and Peter N. Stearns. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2014. 184-203. http://www.jstor.com/stable/10.5406/j.ctt3fh5m1.12 (Accessed 18 November 2020).

MILLAT, Gilbert. Le Déclin de la Grande-Bretagne au xxe siècle dans le dessin de presse. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008.

MITCHELL, W.J.T. What do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2005.

MOLINIER, Pascal. Psychologie sociale de l’image. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 2016.

MONDZAIN, Marie‐José. “Can Images Kill?”. Critical Inquiry 36.1 (Autumn 2009): 20-51. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

MONICO, Reto. “Métamorphose de l’Angleterre dans l’Assiette au Beurre”. Métamorphoses Littéraires. Carnets (Revue électronique d’Études Françaises). Première Série – 5 (2013): 219-251. https://journals.openedition.org/carnets/8528 (Accessed 26 December 2020).

RAEMAEKERS, Louis. Raemaeker’s Cartoons. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1916. Project Gutenberg www.gutenberg.org. Release Date: August 26, 2006 [Ebook #19126] (Accessed 15 December 2020).

RONGE, Peter. “La mise à nu”. Les procédés de déconstruction de l’adversaire. Ed. Bruno de Perthuis. Ridiculosa, 8 (2001): 183-184. Brest: Presses de l’Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

ROSS, Sheryl Tuttle. “Understanding Propaganda: The Epistemic Merit Model and Its Application to Art.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education 36.1 (Spring 2002): 16-30 Chicago: University of Illinois Press. http://www.jstor.com/stable/3333623 (Accessed 2 December 2020).

RUSSELL, Edmund. War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

SASLEY, Brent E. “Theorizing States’ Emotions.” International Studies Review 13.3 (September 2011): 452-476. http://www.jstor.com/stable/23016718 (Accessed 1 November 2020).

La Satire. L’Humour dans l’Art. Revue rétrospective de la caricature mondiale. Volume 1. Imprimerie de “La Satire”: Bruxelles, 1915.

SMITH, James E. “Race, Emotions, and Socialization.” Ed. Jean Ait Belkhir. Race, Gender & Class in Psychology: A Critical Approach 9.4 (2002): 94-110.

http://www.jstor.com/stable/41675277 (Accessed 18 November 2020).

TEULIÉ, Gilles. “The Key to Ladysmith.” Military History Journal 9.4 (December 1993). n. p. Published by the South African Military Society. http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol094gt.html (Accessed 16 December 2020).

TURNER, Jonathan. “Social Control and Emotions.” Symbolic Interaction 28.4 (Fall 2005): 475-485. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/si.2005.28.4.475 (Accessed 18 November 2020).

VEBER, Jean. “Les camps de reconcentration au Transvaal”. L’Assiette au Beurre 26 (28 septembre 1901). 6e édition.

VILANOVA Felipe, Francielle MACHADO BEIRA, Angello BRANDELLI COSTA and Silvia Helena KOLLER. “Deindividuation: From Le Bon to the social identity model of deindividuation effects.” Cogent psychology 4.1 (2017). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311908.2017.1308104 (Accessed 8 July 2021)

Notes

1 1/10th of the Boer population died in the camps because of bad sanitary conditions including many children. The British soldier peeps into a tent and sees two dead children and states “Another two. I will never be able to count them all. People in the War Office will be happy”.

2 Albion comes for Latin alba / albus (white). It was the name given by the Romans to the island after seeing the white cliffs of Dover. The cartoon displays the portrait of King Edward VII as the bare back side of an old and ugly Britannia.

3 Veber published nearly thirty Anglo-Boer War cartoons, twenty-four of which were reproduced in Germany by Dr Eysler, editor of the Lustige Blätter, and twenty-two in the Netherlands by S. L. van Looy in Amsterdam. Later in 1915, Germans published Veber’s anti-British cartoons (except for L’Impudique Albion) in Belgium in La Satire: l’humour dans l’art to remind the French that the English had not always been considered as allies in France. Some of Veber’s Anglo-Boer War postcards were then published in 1931 in “Les Anglais,” a special issue of Le Crapouillot (a French satirical and polemical newspaper born in the trenches in 1915), and were further reproduced in 1941 as anti-British collectible cards in German cigarette packs (Greenwall 224).

4 The title of the cartoon published in the September 1901 issue of L’Assiette au Beurre, is “un foudre de guerre”, which means “a warlord” in French; yet “un foudre” by itself is a wine barrel associated to Bacchus and drunkenness in French popular culture. Of course, a drunken warlord is not a flattering representation of a King.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Gilles Teulié

Gilles Teulié is Professor of British and South African Studies at Aix-Marseille University. He has written extensively on South African history and the Victorian period. He has published a book on the Afrikaners and the Anglo-Boer War: Les Afrikaners et la guerre Anglo-Boer 1899-1902. Étude des cultures populaires et des mentalités en présence (Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry, 2000) and another one on racial attitudes in Victorian South Africa: La racialisation de l’Afrique du Sud dans l’imaginaire colonial (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2015). He is the editor and co-editor of several collections of essays among which: Religious Writings and War (Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry, Les Carnets du CERPAC 3, 2006), Victorian Representations of War (Cahiers Victoriens et Édouardiens 66, Octobre 2007), War Sermons, with Laurence Sterritt (Newcastle-Upon-Tyre, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), Healing South African Wounds with Mélanie Joseph-Vilain (Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, Les Carnets du CERPAC 7, 2009), L’Afrique du Sud, de Nouvelles identités? with Marie-Claude Barbier (Monde contemporain. Presses Universitaires de Provence, 2010) and Spaces of History, History of Spaces with Matthew Graves (E-rea 14.2, 2017 https://journals.openedition.org/erea/5875). He is currently working on the mediatisation of European Empires through early picture postcards.