La voix dans tous ses états

“Circles Surrounding Stars”: The Optics of O in Elizabeth Bishop and James Merrill

Résumé

Cet article explore comment, dans les poèmes d’Elizabeth Bishop et de James Merrill, les figures lyriques constituent leur propre subjectivité à travers l’apostrophe lyrique, ce que j’appellerai ici la langue du O poétique. Plutôt que d’assimiler ce « O » à une tournure vocative, comme cela a pu être le cas dans le passé, je suivrai plutôt la façon dont Bishop et Merrill remettent en question le caractère pluriel, symbolique et iconique des masques que prend l’apostrophe – problématique que l’on peut également assimiler à la tension inhérente à la langue qui existe entre phonie et graphie, entre l’oralité possible du mot et la matérialité de la page écrite.

Abstract

Focused primarily on Elizabeth Bishop and James Merrill, this article is about how lyric speakers constitute their own subjectivity within the apostrophic address or what I consider here as the language of the poetic O. Rather than understand this “O” in a purely vocative way, as has been done in the past, I follow Bishop and Merrill in rethinking its various symbolic, iconic, and material guises—or what we might see as the tension in language between its phonic and graphic existences, between the possibility of the spoken word and the materiality of the written page.

Texte intégral

-

1 All quotations for Elizabeth Bishop are take...

Once up against the sky it’s hard

to tell them from the stars—

planets, that is….1

-Elizabeth Bishop, “The Armadillo,” 103, ll. 9-11

-

2 Lloyd Schwartz corrects the misunderstanding...

-

3 Compare this to P. B. Shelley’s Sonnet [To a...

-

4 In a 1955 letter to Anny Bauman, Bishop expl...

1You’ll recall “The Armadillo,” Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, dedicated to her friend Robert Lowell, in which she describes a Saint’s Day festivity in Brazil where celebrants send fire balloons into the night sky.2 The majesty of the scene—that transcendent beauty toward which artists strive—captivates until we are forced to realize, slowly, through a somewhat detached speaking voice, that the wind sometimes tosses these beauties back toward the earth.3 “It splattered like an egg of fire” (Bishop 22), Bishop’s speaker almost too casually relates, noting how the balloon scorched an owl’s nest, rabbit, and armadillo. The ritual gives way to horror. What appeared to be a harmony of stars ascending toward their heavenly constellations is destroyed, and poetic words themselves, along with the speaking voice and the listening ears, are suddenly and dangerously caught in the crossfires.4 Only then, are we given this final stanza:

Too pretty, dreamlike mimicry!

O falling fire and piercing cry

and panic, and a weak mailed fist

clenched ignorant against the sky! (104, ll. 37-40)

-

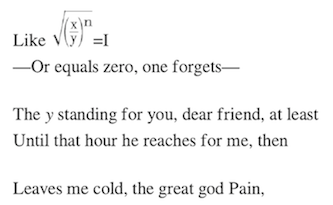

5 Various readers have tried to make sense of ...

2The poetic act—itself “too pretty”—is gusted away and the full, dangerous scope of humanity’s ritualistic actions are exposed to the gasping air of the immediate scene. Amid the non-comprehension of the armadillo, the powerless poet, now with her own ignited eyes, turns away from discursive attempts to capture the scene and begins to address the blazing projectiles themselves: “O falling fire.” Is this the voice of invocation, of resignation, of an exasperated shout against something that doesn’t have ears to listen? What, exactly, happens to the lyric speaker at this moment, and what are we to make of that graphic balloon of an O, which falls a bit too conspicuously into the opening of the antepenultimate line?5 It is within this absence, within this failure of speech to save the animals or even simply to capture the immediate visceral horror of the event, that something like the poetic voice can materialize.

3This article is about such attempts of lyric speakers to constitute their own subjectivity within the apostrophic address or, rather, what I want to consider here as the language of the poetic O. Usually, the O has been understood in a purely vocative way, but I hope to rethink, as poets have done, its various symbolic, iconic, and material guises—or what we might see as the tension in language between its phonic and graphic existences. My focus is primarily on two twentieth-century writers—Elizabeth Bishop and James Merrill, poetic friends for over three decades, whose fascinations with the O inform and complicate modern lyric sensibilities. This is not to suggest that there is a radically new sense of either apostrophe or—gasp—the letter O in the twentieth century; nor is it to imply that Bishop and Merrill are doing something other poets—their contemporaries or those who came before them—haven’t done. Rather, I turn to these poets simply to trace how the often-understated connections between apostrophe and the poetic desire to create might map onto a very different world than the ones in which the lyric found its initial magic. Without trying to be too provocative here, I argue that these poets played with the circular figure of the O (as circle, shout, ring, even a mouth in ecstasy), frequently locating its appearances somewhere between its material and archetypical round shape and what Anglo-European poetic tradition has taught us to understand as the traditional apostrophic address. Accordingly, their lyric voices often find themselves delicately balanced between the possibility of the spoken word and the materiality of the written page. Before conjuring these two poets though, we might, in a circular fashion, feel the need to return to an old tropological climate.

4A scholarly generation ago, apostrophe became a bit of a poetic celebrity, and minor debates about it and metaphorical pushing and shoving brought up some old feuds about the status of poetry and its relationship to the world. Tied to both sentiment and voice, apostrophe, as you know, is the turning away to address another, which is usually an absent person, an inanimate object, or an abstraction. It is sometimes linked with (or confused with) other tropes such as exclamatio (heightened emotion) or prosopopoeia (giving inanimate objects human qualities, notably that of the voice or the ability to hear), or with speech acts, which magically create a sense of temporal immediacy.6 Paul de Man who understood lyric itself as “the instance of represented voice,” was perhaps most responsible for crossing apostrophe with prosopopoeia, “which posits the possibility of the latter’s reply and confers upon it the power of speech. Voice assumes mouth, eye, and finally face” (de Man 1984, 75-76).7 Jonathan Culler has perhaps been the greatest steward of apostrophe over the last generation, linking it to the essence of the lyric itself. He distills this apostrophic energy to the poetic signpost O, as in the celebrated final lines of Yeats’s “Among School Children”:

O chestnut tree, great rooted blossomer,

Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

(Yeats, 217, ll. 61-64)

-

8 For an alternative reading, one which relish...

5The couplings of art and artist, object and voice, which the lines in most readings romantically cast as a metaphysical harmony,8 echo the illusory logic of that simple circular grapheme, which can supposedly do more than offer descriptions of the absent chestnut tree and dancer. In a sense, the apostrophic O seems to gesture toward their actual conjuring, for why else would they be addressed? This is the abracadabric magic of poetry—that a word or even a letter uttered aloud in the right intonation or projected deep into the heavens can somehow change the world. Alas, this kind of appeal too often betrays a hidden desire rather than offer any real linguistic magic. As Seamus Heaney sadly noted, “no lyric has ever stopped a tank” (Heaney 107).

-

9 William Waters (Poetry’s Touch) cautions aga...

-

10 See Culler 2014, 94. Because lyric poems pr...

-

11 The movement from lyric as a genre to lyric...

6Rather than conjure Yeats’s chestnut tree or his mid-swayed dancer, the apostrophic address can voice its own real hopefulness, suddenly overwhelmed by an unexpected awareness. This, perhaps, is the partial magic of the trope. But does “O,” as Culler suggests across different venues over the years, automatically invoke the apostrophe? Other critics, such as J. Douglas Kneale and William Waters, have rejected the passionate O as apostrophe (preferring the Greek term ecphonesis) and rejected the conflation of apostrophe with prosopopoeia or anthropomorphism, which are more about animation than “turning away” in order to address anew.9 Kneale writes, “The current problem with apostrophe stems from associating it with voice rather than with a movement of voice” (Kneale 142). In essence, we can have prosopopoeia without apostrophe and apostrophe without prosopopoeia. It can seem a bit trivial to find “apostrophe” with each turn of the O—“the most sonorous vowel” (Poe 157), as per Edgar Allan Poe—as if every time one were to eat a bowl of Cheerios, one would encounter Oatic nature itself speaking. The criticisms of Culler are not unwarranted, but they do seem to miss both the thrust and delight of his intervention, which hopes to recapture the enunciative structure of the lyric address.10 Here, the force of tradition and the expectations associated with cultural experience come into play, even if we were to move away from the sense of lyric as genre.11 Mark Smith writes, “where there is lyric, there is apostrophe… [which] names not a codified rhetorical device or trope, but a demand that lyric poems lay upon their readers” (Smith 411). Most interesting, perhaps, is that the voiced nature of apostrophe disrupts our understanding of lyric privacy—what we have come to think of, in the last couple hundred years, as an utterance that is somehow “overheard.”

7It is difficult, perhaps, in our contemporary age to take the poetic posturing of, say, “O chestnut tree” seriously. The lines themselves even seem to force their iterator into a physically different face, one which needs to eyebrow-raise a feigned seriousness or otherwise half-smirk at the fabricated utterance. Culler, too, has been acutely conscious of apostrophe’s tendency to provoke a feeling of embarrassment. This is, after all, an outdated poetic trope, which forces its listeners not toward laughter or tears, not toward ecstasy or terror, but toward eye-rolling amid titters for an age of belief that certainly never quite existed as we conjure it now. Apostrophe is “the pure embodiment of poetic pretension,” he writes (Culler 2001, 143), noting how “the craft of poetry would be demeaned if it were allowed that any versifier who wrote ‘O table’ were approaching the condition of sublime poet” (152).12 The embarrassment is such that, in a line of Wallace Stevens cited by Culler, the modern poet wants nothing to do with it: “…apostrophes are forbidden on the funicular.”13 Despite the embarrassment of apostrophe, despite what Culler—tongue-in-cheek—finds as the tendency of literary critics to “turn aside from the apostrophes they encounter in poetry” (136, emphasis my own), Culler can still isolate apostrophe as the central trope of the lyric, precisely because it will not allow for the easy reduction of poetry to paraphrase: “Apostrophe resists narrative because its now is not a moment in a temporal sequence but a now of discourse, of writing” (152). The poet, as in the opening example from Bishop, turns away from her descriptions on the page to cry out a loss, and thereby constitutes, in the process, her own lyric subjectivity.

-

14 “To apostrophize is to will a state of affa...

8Apostrophe, for Culler, has to do with the vocative, with vocal performance, and with a distinctive lyric temporality. It “makes its point by troping not on the meaning of a word but on the circuit or situation of communication itself” (135), focusing us on the moment of discourse, rather than the time of narrative, belying the story one wants to tell (or tell oneself) with the sudden conscious realization that one is speaking, perhaps to no end. It is not simply the demonstration of a moment of realization, however, that has grabbed one’s attention. Suddenly, poetry becomes magical. “To apostrophize,” Culler writes, “is to will a state of affairs, to attempt to call into being by asking inanimate objects to bend themselves to your desire” (139).14 In this, the performativity of the apostrophic gesture is very close to onomatopoeia, where, supposedly, voicing means doing.

9P. B. Shelley’s “O wild West Wind,” for example, does not describe but rather invokes the wind, or, more precisely, invokes a voice hoping to invoke the wind:

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being!

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing….

(Shelley, 401, ll. 1-3)

10Linguistically speaking, there ought to be little distinction between the poet/speaker uttering those words and their iteration today. The wind hasn’t actually been conjured, but a voice reaching out to it (and accordingly failing to reach it) has. “What is really in question,” Culler writes, noting W. H. Auden’s famous elegy for Yeats, “is the power of poetry to make something happen” (Culler 140):

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

(Auden, 248, ll. 35-41)

-

15 Does poetry, Sara Guyer asks, “survive as a...

11It is one of the most mis-contextualized poetic lines of the 20th century: “poetry makes nothing happen.” The “surviving” poetry seems to make quite a lot here: valleys, rivers, and then ranches and towns—the event of the poem itself becomes its own happening.15 This is the performative magic that draws Culler to the trope: “Nothing need happen because the poem itself is to be the happening” (149). And, it is a happening that, in an extended conceit running throughout the poem, is effected by the possibilities of the “mouth.”

12One would be remiss if one did not mention the speaker’s initial pang about the febrile earth and its lamenting “O,” which has been lost to history but can still linger. Auden changed the original refrain in the first part of the poem (“O all the instruments agree / The day of his death was a dark cold day”) to the more familiar one seen today: “What instruments we have agree / The day of his death was a dark cold day” (247, ll. 5-6). In both versions, notwithstanding, the lines suggest a thermometer placed in the open mouth of the day, a mouth reshaped into its own O to receive the instrument. The speaker seems to engage in the pathetic fallacy, believing that the earth, too, is so stricken by this loss as to bring about a coldness across its face. But the earth, no more than the plaints, as Skeeter Davis will always remind us, cannot change the weather.16 Paradoxically, the act of revising seems to belie the artifice of the whole enterprise, the falsehood of the voice of anguish; the poet is calmly choosing one refrain instead of another, not, in any way, burdened by the moment. It is as if the Hollywood director, following Wordsworth’s admonitions in the “Preface,” were shouting into her bullhorn: “O isn’t real! Use fewer poetic devices to get authenticity!” Still, we might ask, is it all artifice? Although the apostrophic address cannot create the deaf object being hailed, it can (and does) fashion the voice hailing it, which, in Auden’s poem, seems to be a voice in anguish at its own inabilities to change the season or summon the departed. It is the address to the Other, which constitutes the speaker.17

13We have something like this—although the uncertainty of the voice cannot be resolved—in Bishop’s “In the Waiting Room,” which dramatizes a young girl’s trip with her aunt to the dentist’s office. While reading a copy of National Geographic in the titular waiting room, she hears “an oh! of pain,” which comes ambiguously from the “inside.” Is this the inside of the dentist’s room where her aunt is being treated or the inside of herself? Here, a shared closeness, a shared womanhood navigates that valley between addresser and addressee:

… What took me

completely by surprise

was that it was me:

my voice, in my mouth.

(160, ll. 44-47)

14It might also be important to note at this juncture, (if only to turn quickly and address Jacques Derrida), the perhaps-more-than-graphic distinction between “O” and “oh”—what, at another time, the philosopher might have called “this sameness which is not identical.” As Barbara Johnson relates, the “O,” which carries with it the long years of poetic ritual, is usually seen as “pure vocative,” and the “oh” as “pure subjectivity”; the first gives us the illusion that the “you” is created; the second gives us an illusion of the “I” (Johnson 187).

15Oftentimes, it feels as if the only actual magical conjuring of apostrophe would be in its failure. Consider, briefly, Walt Whitman’s “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking,” where the mockingbird’s apostrophe for his lost love goes unanswered: “O throat! O throbbing heart! / And I singing uselessly, uselessly all the night…. / But my mate no more, no more with me! / We two together no more” (Whitman, 176, ll. 123-24; 128-29). The conjuring, the attempt to voice a thing into being fails, but in doing so brings about the immortal presence in the boy of “a thousand warbling echoes… never to die” and a sense of self-identity that hadn’t existed before. Or we might think of George Herbert’s heavenly phone call, “Deniall”:

When my devotions could not pierce

Thy silent ears,

Then was my heart broken, as was my verse….

“Come, come, my God, O come!

But no hearing.”

O that thou shouldst give dust a tongue

To cry to thee,

And then not hear it crying! All day long

My heart was in my knee,

But no hearing….

(Herbert 2007, 288, ll. 1-3; 14-20)

-

18 Apostrophe is, per Val Cunningham, “the fun...

-

19 Herbert: “When he preacheth, he procures at...

-

20 Gavin Hopps writes, “faith has its being an...

16As the unrhymed final line of each of the stanzas but the last makes clear, there is no responsive echo from the one the speaker is reaching out toward. God, in a sense, has swiped left. The poem hinges on this failure of apostrophe. That is until the hopeful final lines (“They and my minde may chime / And mend my ryme” [289, ll. 29-30]), when the sound of the Word begins harmonically to resonate in the concluding rhyme. Then again, we might wonder whether the echo of one’s own words really means that someone is listening or question whether the act of calling out really conjures a divine presence. Is this turn to address poetic conjuring or a mere example of wish fulfillment? Prayer, of course, is the greatest of all apostrophic acts, and Herbert was not unaware of its theological possibilities.18 When he writes of the effectiveness of sermonizing in A Country Parson, and lists the five characteristics of “Holiness,” he includes, among others, “making many apostrophes to God.”19 But is this act of apostrophe—or what de Man would here see as prosopopoeia—more than just a quick rhetorical trick? O ye, of little face. Sincere faith presupposes the authenticity of the communicative exchange following the ritualistic address. Making any presumption about the efficacy of this speech act would already mean having resolved a theological debate.20 Were one to believe in such power of words, though, one might find its counterpart in divine power: God, as the story goes, utters the word “light” and light appears.

17Turning to another fruitful failure of apostrophe, Culler invokes Charles Baudelaire’s “Le Cygne”: “Eau, quand donc pleuvras-tu? quand tonneras-tu, foudre ?” (160, l. 23). Culler writes, “when it seeks something other than itself (eau), it finds only itself (O), which may also be nothing (O)” (144). Here, the swan’s failure to conjure rain (much ado about nothing) is the poet’s failure to conjure anything with mere words, but, like Whitman’s mockingbird, the inability to summon becomes a type of enactment, which allegorizes the empty process of signification: cygne becomes signe. It is a swan song, no doubt, but one which is, perhaps, enchanted in unintended ways, despite the parched tongue of language.

-

21 For now, I will defer the deeper discussion...

18I follow Culler in connecting the vocative O to the tensions, presumptions, and possibilities of the lyric form itself. Wary as I am of reinventing the wheel, I hope to grasp the circularity of this turning address as it exists between trope and sign, between the illusion of voice and the graphic on the page, between metaphysical longing and the texture of language. Without venturing too far into the logic of the logos, it is safe to say that the phonocentric critical understandings of the apostrophic act have presumed a presence—either that of the speaker mid-address or the reader reenacting the “original” address.21 The written word—an unrealized potential, lingering until spoken—cannot be “magical” unless it is vocalized, unless it is translated into speech. Against this phonocentric logic, I hope to capture here some of that apostrophic magic, as it exists on the page. Many twentieth-century poets, acutely aware of both the possibilities and embarrassment of apostrophe, have played wonderfully in this poetic space. James Merrill and Elizabeth Bishop are two of them.

* * *

Ken had us break the circle and repair

To “a safe place in the room.”

(Merrill, “Family Week at Oracle Ranch”, 657, ll. 85-86)

19The presumption with any oracle (from the Latin “to speak”) is that the gods would take the time to turn away from their godly affairs to tell some people what is in store for them. Seeing, though, how often the gods invested themselves in the affairs of humankind (usually for their own political or personal machinations), such condescension is not unimaginable. When Merrill arrives at “Oracle Ranch,” a modern rehabilitation center in what is feasibly Arizona, he is struck by a different sort of condescension. The group circles, he describes (in the epigraph above), provide more counsel (however clichéd) than forecasts, but the known threat of a possible future still lingers overhead.

20“Family Week at Oracle Ranch” chronicles the poet’s visit to see his friend and former partner, David Jackson. Mirroring the 12-step program, the poem is in 12 parts, each seemingly its own hour on a clockface. Each part is four stanzas long, the first and final lines of the stanza rhyming, thus, as it were, completing the circle. Initially, Merrill seems to be poking fun at the unaware earnestness of the “new age” scene—what Langdon Hammer calls a mix of “hallmark-style sentimentality and cynical realism” (Hammer 757). The psychotherapeutic gods of old (“Underwear made to order in Vienna” [l. 14]) are nowhere to be found, replaced here by the wonders of Benetton (“stone-washed, one size fits all” [l. 16])—an apt wink at both the stanza form and Merrill’s own conversational tone—and a brochure featuring a “wide-angle moonscape, lawns and pool” (l. 6). Although the circle might be reminiscent of the séances those in Merrill’s circle were familiar with—other manners of apostrophic summoning—he is reluctant at first to engage with the counsellors, or as he calls them “deadpan panels” (l. 42). The poet’s vocabulary (and emotions) are reduced to the seven words allowed in the circle: “AFRAID / HURT, LONELY, etc.” (ll. 17-18). On other occasions, the poet has been asked to do more with less—say with the six words allowed in the sestina—but the reticence here is cutting. The poet learns “Not to say / ‘Your silence hurt me,’ / Rather, ‘When you said nothing I felt hurt.’ / No blame, that way” (ll. 21-24). Interestingly, in calling attention to the things that would not be spoken (what “family” entailed to the public, the AIDS diagnoses), the corrected lines bring the turn of address inward, to the wounded subject rather than the “you” who would not respond.

21Memories of the past (“In great waves it’s coming back” [l. 55]) and future apprehensions (“In a flash I saw // My future” [ll. 76-77]) circle around. Merrill is asked to envision “home”—that locus so central to his earliest scripts. The word, of course, cannot conjure Merrill’s childhood home, but it can call up a whole nest of memories in the poet’s imagination: “Years have begun to flow // Unhindered down my face. Why? / Because nobody’s there” (ll. 108-110). Emptiness, it seems, can be conjured. If poetic apostrophe is about holding on, Oracle Ranch is about letting go: “Let go / Of the dead dog, the lost toy” (ll. 114-15), the “GUILT” from an insignificant moment half a century ago. After being castigated for thinking himself “terminally unique” (l. 168)—a frightening paronomasia, given Merrill’s diagnosis—the speaker wonders “if it were all like the moon” (l. 177), thereby circling back, or “recover[ing]” his image from the poem’s opening. The final lines expand the simile and seem to imply that recovery (amounting to “self-forgiveness”) is more a tidal ebb and flow of falling down and standing up than ever being re-composed. The speaker, in a self-address, writes, “Ask how the co-dependent moon, another night, / Feels when the light drains wholly from her face. / Ask what that cold comfort means to her” (ll. 190-92). The self-effacing co-dependency, a cycle of need between the moon and earth—orbs in the sky, forever pulling at each other—leads in Helen Vendler’s words to “a rueful acknowledgement of the elementary nature of feeling, no matter how elaborate its eventual transmutation into art” (Vendler 206). Personified here, but un-addressed, the moon occasions the speaker’s own final silence. Rather than the earlier consumer-mediated “moonscape” of the brochure, the mesmerizing shape of this final moon and its hints at a lifetime of circularity—however eye-rolling such clichéd humanistic tropes seem to be—constitute the speaker’s lyric subjectivity, which is ironically grounded in the inability to voice an answer.

22 Merrillean cycles of the moon appear again in “b o d y,” a neighboring poem in A Scattering of Salts, his final collection:

Look closely at the letters. Can you see,

entering (stage right), then floating full,

then heading off—so soon—

how like a little kohl-rimmed moon

o plots her course from b to d

—as y, unanswered, knocks at the stage door?

Looked at too long, words fail,

phase out. Ask, now that body shines

no longer, by what light you learn these lines

and what the b and d stood for.

(646, ll. 1-10)

23What happens when the words we use to understand our world suddenly lose all sense because they are too saturated with meaning? As if they were four actors on the stage of life, the letters “b” “o” “d” and “y” perform, but never long enough. The movement of “o” from one line of life to another reminds Merrill of the phases of the moon and then to a maquillaged face ready to perform. In the final line, we are asked to answer the riddle of existence. “B” we might take as “birth,” “D” as “death”—the lines of life, between which O moves. “Y” or “why” (which stands outside the lines of life) gives us a final pun, but the joke is on us—we who are conjured by the verse—as we try to listen for an answer (what does it all mean?) that will never come.

24Just as the moon phases out, words fail, but the failure of this word—“body”—carries with it grave consequences. What does one lose when one looks too closely at letters? (It is not only the anti-formalist who seeks this answer!) One does not have to know Merrill well to know that his figuration was always more trope than body. It is false to claim, though, as some readers of his have done, that the two, for him, are distinct. He is not an obviously plaintive poet, but pain does hide in his penumbras. “Can you see…?” the first line asks. Can U C? An unfinished circle of a letter tips over, as a body on stage. And what about all those pregnant Os and double OOs (look, so soon, moon, door, looked, too long, stood), which vie for the spotlight? Underlying all this harmless fun with word puzzles and games lies a glimpse into the dark recesses of our staged being and the failure of lettered attempts to recover the world.

-

22 Syrinx is also a dangerous watery build-up ...

25If the movement of o from b to d constitutes our lives, the simple letters “I” and “O”—a line and a circle—become in “Syrinx” a binary of being and oblivion. It is a staggering poem, one of Merrill’s best. Coming to terms with a friend’s diagnosis and treatment—the cure, as the pedestrian saying goes, is worse than the illness—Merrill looks back to the myth of the nymph Syrinx. Pursued by the god Pan and terrified by his sexual advances, she flees to the waters and cries out for help. Her cry—its own conjuring of sorts—is heard and she is transformed into water reeds, which Pan, ever the lecher, eventually fashions into his panpipes—also called syrinx today.22 As a reed, Syrinx trembles, her movement dependent on the volition of the wind. No hands with which to write, no voice with which to speak, her only mark can come as the illiterate’s X of crossed reeds. The tragicomedic pun of the poem sounds in what Stephen Yenser calls a “muffled solfeggio” (185): “Who puts his mouth to me / Draws out the scale of love and dread— / O ramify, sole antidote!” (Yenser, 355, ll. 7-9)—the scales, perhaps balancing more toward dread. We celebrate natural proliferation perhaps too often in our readings of poetry. Yet it is such proliferation, such ramification that the “fatal growths / Proliferating by metastasis / Rooted their total in the gliding stream” (ll. 10-12) bring. The word “rooted,” itself ramifying, then leads to the formula of a “square root” (something cut down by its own number). This “formula, not relevant any more,” gives us (almost in perfect iambs):

(ll. 15-19)

26Does the formula equate to “one” or the “I” no longer with a voice? No matter, it might have been zero after all. One forgets. The X, we know from line 6 (“Illiterate—X my mark”), is the speaker. The Y—attached at the hip but separated by a bar—stands for “you.” If we take the “S” and the “R” from “square root” and add them to the letters in the equation (X, Y, N, I), we are left with an anagram for “syrinx”—another metamorphosis, another transformation. Caught in its own airstream, the poem concludes with a circular compass:

Or stop the four winds racing overhead

Nought

Waste Eased

Sought

(356, ll. 25-8)

-

23 Merrill’s fascination with the O does not e...

27How are we to read the wood-winds of these final lines? Linearly? Moving from the zero of “nought” to a hopeful “sought”? “Nought, waste, eased, sought”? Normally, we would voice the directions as “Nought, sought, eased, waste,” but this would compel us to break the poetic line and jump through the page. Rather than a circle or an “S,” we would invoke the winds as a cross, perhaps more charitable than the earlier “Christian weeds,” for they blow us between one and zero, between nothingness and possibility, between our wasting bodies and whatever can alleviate the pain.23

28O is a symbol that performs for Merrill, and it’s hard to detach its meaning from an archetypical history that is continually informing the verse. Beyond the invocation or the excited utterance, beyond nothingness, we have the circular shape of the sun and the moon and the face and the metaphorical seasonal cycle, which on one hand gestures toward rejuvenation but on the other signals the final movement toward the end. Linked to each other etymologically (κύκλος), the circle and the ring seem to go together for Merrill. As Andrea Mariani argues convincingly, rings “signify the transmission of a heritage, the reification of a promise… The ring can be priceless, not so much because of its stone setting, but because it belongs to a dynasty and represents the stratification of a family history…” (Mariani 63). Wagner’s Ring Cycle, a great early influence on Merrill, leaves him meditating on how his three rings carry the weight of more than their material substances. The ancestral meaning of the ring appears again in “The Emerald,” the heartwarming second part of the diptych poem “Up and Down,” a modern katabasis, which takes Merrill and his mother down in the bowels of the earth to a bank vault. She wants to give her son a ring, for when he marries, for his bride. Of course, Merrill—as both he and his mother know but cannot voice—will never take a bride, but the awkwardness of the failed gift is alleviated once Merrill, who doesn’t want to sound “theatrical,” softly slips the ring back. All the while, prosodic puns on feet pattering and the underground room—a hermetic “stanza”—show that the possibilities of a heritage exist as much in the poetic line as in the familial one.

29Unanswered, apostrophe rings hollow. Such is the case in Merrill’s circular villanelle, “Dead Center”:

Upon reflection, as I dip my pen

Tonight, forth ripple messages in code.

In Now’s black waters burn the stars of Then….

Breath after breath, harsh O’s of oxygen—

Never deciphered, what do they forebode?

In Now’s black waters burn the stars….

(540, ll. 1-3, 13-15)

30Existing between prophetic knowledge (in the villanelle, one knows how things will end) and the juggernaut of time (in the villanelle, one is given only a 19-line reprieve before the end), the villanelle can be a terrifying exercise.24 Is the “Then” of the second refrain a past then or the then that is soon approaching? The black waters of the sky burn with the stars of a past then, because, when searching the night sky, one is always looking into the past lives of stars lightyears away, stars which not insignificantly have been taken in the past as premonitions. These black waters might also allude to the poet’s inkwell, another sort of upside-down reflection, already conjuring its own end with the pen dip of the opening stanza. The Wallace Stevens-esque attempt to get at the cold, ignorant nothingness of immediate experience brings us (wink-wink) “deeper into Zen” (l. 7). The immediacy that Merrill is blowing on, though, feels more like the end of a cigarette, and its smoke-rings mask the “Breath after breath, harsh O’s of oxygen” (l. 13). Reduced to its elemental sign O (here acting on the one hand as poetic inspiration and on the other as the very basis of human life), the code remains uncracked or, rather, “never deciphered.” “Cipher” derives from the word zero, which in turn, comes from the word zephyr.25 What does it all mean? The wild West Wind will not reveal itself at Merrill’s call. Finally, it is not the vocative O but the resigned “Ah,” which signals the turn to the apostrophic address to Memory itself at the end:

Ah then

Leap, Memory, supreme equestrienne,

Through hoops of fire, circuits you overload!

Beyond reflection, as I dip my pen

In Now’s black waters, burn the stars of Then.

(ll. 15-19)

31If memory is what constitutes our subjectivity (we are because we know who we once were and who we might become), what would it mean, given the repeated refrains of the villanelle form, to turn to address “Memory”—an addressee tied as much to foreknowledge as recollection? Constituted somewhere in the blazing horseplay between the graphic and vocative, Merrill’s lyric subjectivity is invoked in this multitemporal “now.” Thus the memory at the close of stanza one (that then) then returns, overloaded and brazenly leaping through hoops of fire to get back through the overloaded rings of the mind to where it once was.

* * *

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

(Bishop, “One Art” 178, ll. 16-19)

-

26 Bishop’s father died when she was an infant...

-

27 There are sixteen known versions, some unti...

-

28 Diehl and Mutlu Blasing stress the connecti...

32Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” famously aestheticizes loss, which was too much of a theme of Bishop’s life.26 “Write it!” the final line exhorts, and she did, over and over again. Bishop revised this poem considerably through the years, finally settling on the formally intricate villanelle form.27 The poem asks us to understand “losing” as an artform, and accordingly brings together the rhyme “master” and “disaster” in its refrains. It is an odd analog, where life seems to be pit against art. For Joanne Feit Diehl, the “mastery sought over loss in love is closely related to poetic control…. ‘One Art’ presents a series of losses as if to reassure both its author and its reader that control is possible—ironic gesture that forces upon us the tallying of experience cast in the guise of reassurance” (Diehl 96).28 Like Merrill, Bishop navigates between the one of the titular art and the zero of loss, and she is quite playful with her refrains. For example, “to be lost that their loss is no disaster” (l. 3) becomes “to travel. None of these will bring disaster” (l. 9) becomes “I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster” (l. 15). In a sense, Bishop formally loses her way as she goes, such that, at the end, whether out of “forgetfulness” or boredom or poetic constraint, she must force herself to the known conclusion (the lines epigraphing this section).

-

29 Colwell writes, “This duality that Bishop w...

33One takes the apostrophe at the end ironically, as it is a turn to address something that, as even the speaker seems to acknowledge, will not reappear. Beyond “the joking voice,” the “you” acts as a shield, concealing all the people Bishop had lost—most notably her recent companion Alice Methfessel (who, like a poetic refrain would soon return). The “you” also feels as if it doubles back on the “I,” which, after lines and lines dedicated to loss, now feels empty. The final refrain has the poet addressing herself with what seems to be a joking voice, demanding that she—forgetful, tired, lost—still complete the circle.29 We might understand this hesitation psychologically as a lyric speaker unwilling to deal with loss or meta-poetically as a wonderful commentary on the tedium and expectation (and possibly hopelessness) of the villanelle form. It is a victory of sorts—completion, but is this suggestive of a personal (rather than poetic) mastery over the psychological and somatic or a more modest desire just to see things end? How ever one understands these final lines, they gesture toward the sense that lyric subjectivities—rather, our very identities are constructed and reconstructed over and over through the slowly changing refrains of experience mediated by the voiced possibilities of language.

34We see Bishop’s serious playfulness again in her “Four Poems,” a short sequence, which plays a bit on the sonnet form and is about the often-failed attempts of lovers to communicate. The first poem “Conversation” focuses on the lover’s “tone of voice” (76, l. 4) and the hope that language can conjure more than the empty pleading of the speaker. For lovers, as for poets, finding the right word can change everything. If only language (be it onomatopoeia or prayer or apostrophe) had such performative magical abilities to map name onto meaning: “And then there is no choice, / and then there is no sense; / until a name / and all its connotation are the same” (76, ll. 9-12). The fourth poem in the sequence, the sensual, mysterious, corporeal Anglo-Saxon mock-up “O Breath” shows the very bodily under skin of language:

Beneath that loved and celebrated breast,

silent, bored really blindly veined….

Equivocal, but what we have in common’s bound to be there,

whatever we must own equivalents for,

something that maybe I could bargain with

and make a separate peace beneath

within if never with.

(79, ll. 1-2, 11-15)

-

30 Lombardi writes, “the difficulty and restra...

35The voiced opening demands that we hear “breath” in “breast”; they move together, both involuntarily. The harmony, though, is not always there when the breast is not your own. Here, the breathing is attended to with a caesura, as if the line itself needed to wait for the next inhalation, or perhaps inspiration. The silent voice in the middle of the lines operates within what Marilyn May Lombardi calls a “rib cage of words” (Lombardi 33). Lombardi notes the similarities between the poetic act and Bishop’s debilitating asthma: “[t]he poem’s gasping, halting rhythms and labored caesura mimic the wheezing lungs of a restless asthmatic trying to expel the suffocating air” (33) and reads this difficulty of voicing alongside the mid-century social obstacles facing the female poet.30 It is an unusual poem—more about resignation than passion, and certainly not quite what one would imagine from the apostrophic title, which seems to call out to join a whole overromanticized poetic tradition. Oddly, the poem’s specificities lead the speaker into universality, or at least a hope for one, as the intimate moment is grasped, yet not permanently—a recurring sentiment in Bishop. Her meditation in language—this talking through something—becomes its own lyric conjuring of sorts—desire, writ small. One is left with questions. Will the sexual act, with its involuntary breaths, voiced hesitations, and erotic ohs follow? No choice, no sense in the sounds, but the understanding that the name and connotation of a voicing might finally be the same.

36During the winter of 1935-36, le temps juste avant la guerre, Bishop was in Paris. Her poem “Paris, 7 A.M.” was written later that year, just after Hitler moved into the Rhineland, and it was published in 1937. The first stanza begins:

I make a trip to each clock in the apartment:

Some hands point histrionically one way

And some point others, from the ignorant faces.

Time is an Etoile; the hours diverge

So much that days are journeys round the suburbs,

Circles surrounding stars, overlapping circles.

The short, half-tone scale of winter weathers

Is a spread pigeon’s wing.

Winter lives under a pigeon’s wing, a dead wing with damp feathers.

(26, ll. 1-9)

-

31 Given the tonal echoes throughout and the a...

37The poem brings the speaker into the shadow of the upcoming war, which hangs metaphorically over the city in the half-tone winter grays of a pigeon’s wing. The poem is very much about the speaker who, through the architectural turns of the city, attempts to process this dreadful uncertainty. While the poem delves in and out of the speaker’s present, past, and imagined future, it strangely only uses the word “I” once—as the initial word of the poem. The clocks are in disarray and time is more than metaphorically out of joint. The speaker personifies the clock’s faces and hands, understanding them to be “histrionically” gesturing. The ramifying hour leads the speaker to see time itself as a star, an image which is then mapped onto the cityscape. David Kalstone reminds us of the circular layout of many Paris avenues, which Bishop would have seen outside her apartment window (Kalstone 45). Those familiar with Paris will also recognize the Place de l’Étoile (now renamed “Place Charles de Gaulle”), around which twelve streets, including the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, meet, as though at the center of a clock face. The Champs-Élysées and the Arc de Triomphe (which stands in the middle of the square) are war memorials—the Champs-Élysées, named after the mythological Elysian Fields, and the Arc de Triomphe, itself often encircled with famished pigeons, memorialize those who died in the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. Because, when viewed from above, the intersection resembles a clock, the remark that “the hours diverge / So much that days are journeys round the suburbs” (ll. 4-5) feels more like a guide to navigate the urban space than a passing reference.31 The circular paths of the hour and minute hands, as well as the labyrinthine nature of the city itself create “overlapping circles,” but here such intersections might ominously resemble those territories claimed by different national powers, say the overlapping circles in two national memories of Alsace-Lorraine.

38The speaker commands herself discursively (or turns to command her audience) to “Look down into the courtyard” (l. 10), reminding us (and herself) that we are not in a poetically “timeless” or “universal” poetic place but really here, now. The metaphorical pigeons of stanza one return as literal birds atop the mansard roofs and beside the ornamental but threatening urns. The sight will soon force her circular memory, in a fascinatingly ambiguous phrasing, into something “like introspection”:

It is like introspection

To stare inside, or retrospection,

A star inside a rectangle, a recollection:

This hollow square could easily have been there.

—The childish snow-forts, built in flashier winters,

Could have reached these proportions and been houses;

The mighty snow-forts, four, five, stories high,

Withstanding spring as sand-forts do the tide,

Their walls, their shape, could not dissolve and die,

Only be overlapping in a strong chain, turned to stone,

And grayed and yellowed now like these.

(ll. 13-23)

39What a fascinating simile or almost-simile at the heart of this poem—that looking into the traces of your own mind is like trying to look into someone else’s apartment. The spatial simile (akin to the concentric circles of inner identity) is rethought temporally as a “retrospection” and then spatio-temporally as a “recollection.” These internal attempts to get at the meaning of the scene also aptly describe the concentric circles of repeated sounds (“stare,” “star,” “square”), as Eleanor Cook notes (Cook 46). Is the “hollow square”—a conjuring of absence—a memory that can’t be reconciled with the speaker’s present thoughts? Is it the speaker’s lapsed perception? Her apartment? An empty Paris street in winter? A reference to an empty space across the way describing something that is no longer there? In a lighthearted moment, such retrospection teases the speaker into a memory of her New England winters, brighter in the back of her mind than what she is seeing now. The future still looms, and even those “flashier” memories circle back to the anxieties of the present and eerily foreshadow the games of war that the adults will play:

Where is the ammunition, the piled-up balls

With the star-splintered hearts of ice?

This sky is no carrier-warrior-pigeon

Escaping endless intersecting circles.

It is a dead one, or the sky from which a dead one fell.

The urns have caught his ashes or his feathers.

When did the star dissolve, or was it captured

By the sequence of squares and squares and circles, circles?

Can the clocks say; is it there below,

About to tumble in snow?

(26-27, ll. 24-33)

40Expanding and then half-rejecting her own metaphor, the speaker concludes that the sky is not the messenger-hero of a wartime carrier-pigeon, but a dead one. Syntactically, the lines become confused; the metaphorical sky, as it were, is turned upside-down, and the pigeon seems to fall from its own metaphor. Like tokens atop a board game, the shapes of squares and circles move to surround and capture the stars. Finally, at the end, we come back to the opening clock, which now has a deceptive face. Like in the villanelles, we must wonder whether time is really moving or whether we, like the speaker, are just frozen in a singular sensibility.

41“Where is the ammunition, the piled-up balls / with the star-splintered hearts of ice?” (ll. 24-25). She might as well have been asking Mais où sont les neiges d’antan! This invocation of absence voices desire but it is one which runs down from the hills of yesteryear. Earlier, I argued that within the failure of speech to conjure, something like the poetic voice can emerge. It might be circular logic, but this “presence” of voicing assumes a mouth and an already constituted lyric subject. Adding a temporal dimension grounded in the sign to the presumed “now” of the vocative would mean that apostrophe—what I have understood here as the constituting act of lyric subjectivity— cannot be understood only in its immediacy but rather, to turn a phrase, must somehow also be recollected in tranquility. The poet and the reader may each utter the apostrophe anew, and in turn constitute and reconstitute a voice, but that invocation must linger as a voice unheard perhaps for centuries, enduring in the potential of the written sign to circle back, as it were. Poets have danced around this lyric circus—that lifetime between zero and one—in countless ways. At times, Merrill and Bishop play with a subjectivity caught in the paradoxical temporality of the villanelle refrain; other times, they look through the circle to seek out the wealth that emptiness can hide.

42Thankfully, there is no zero on the analog clock. The clock will always return to 1. Then again, as Bishop warns, history ought not be subject to its own lived retrospection. You’ll recall, that that’s the hope of the monument—perhaps more the poetic one than the marble one: to remember so that time (oh time!) could move along to warmer places.

Bibliographie

Auden, W. H. Collected Poems. Ed. Edward Mendelson. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Baudelaire, Charles. Selected Poems from Les Fleurs du Mal. Trans. Norman R. Shapiro. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998.

Bellos, Alex. Here’s Looking at Euclid. New York: Free Press [Simon & Schuster], 2010.

Bishop, Elizabeth. The Complete Poems 1927-1979. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983.

Blasing, Mutlu. American Poetry: The Rhetoric of Its Forms. New Haven: Yale UP, 1987.

Colwell, Anne. Inscrutable Houses: Metaphors of the Body in the Poems of Elizabeth Bishop. Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 1997.

Cook, Eleanor. Against Coercion: Games Poets Play. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1998.

Costello, Bonnie. Elizabeth Bishop: Questions of Mastery. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1991.

Culler, Jonathan. “L’Hyperbole et l’apostrophe: Baudelaire and the Theory of the Lyric.” [Time for Baudelaire] Yale French Studies 125/126 (2014): 85-101.

Culler, Jonathan. The Pursuit of Signs. Augmented ed. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2002.

Culler, Jonathan. “Reading Lyric.” [The Lesson of Paul de Man] Yale French Studies 69 (1985): 98-106.

Culler, Jonathan. Theory of the Lyric. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2015.

Cunningham, Valentine. In the Reading Gaol: Postmodernity, Texts and History. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1994.

Davis, Skeeter. “The End of the World” [written by Kent, Arthur and Sylvia Dee]. Skeeter Davis Sings the End of the World. RCA Records, 1962. LP. A-side.

de Man, Paul. Allegories of Reading. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979.

de Man, Paul. Rhetoric of Romanticism. New York: Columbia UP, 1984.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1974.

Diehl, Joanne Feit. Women Poets and the American Sublime. Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1990.

Doreski, C.K. Elizabeth Bishop, The Restraints of Language. New York: Oxford UP, 1993.

Guyer, Sara. “Wordsworthian Wakefulness.” Yale Journal of Criticism 16.1 (Spring 2003): 93-111.

Hammer, Langdon. James Merrill: Life and Art. New York: Knopf, 2015.

Hartman, Geoffrey. Beyond Formalism. New Haven: Yale UP, 1970.

Heaney, Seamus. The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose 1978-1987. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988.

Herbert, George. “The Country Parson.” The English Works of George Herbert, vol. 1. Ed. George Herbert Palmer. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1905. 193-323.

Herbert, George. The English Poems of George Herbert. Ed. Helen Wilcox. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007.

Hopps, Gavin. “Beyond Embarrassment: A Post-Secular Reading of Apostrophe.” Romanticism 11.2 (July 2005): 224-241.

Jackson, Virginia and Yopie Prins, Eds. “Lyrical Studies.” Victorian Literature and Culture 27.2 (1999): 521-30.

Johnson, Barbara. “Apostrophe, Animation, and Abortion.” A World of Difference. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1987. 184-99.

Kalstone, David. Five Temperaments: Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, James Merrill, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery. New York: Oxford UP, 1977.

Keniston, Ann. “The Fluidity of Damaged Form: Apostrophe and Desire in Nineties Lyric.” Contemporary Literature 42.2 (2001): 294-324.

Kneale, J. Douglas. “Romantic Aversions: Apostrophe Reconsidered.” ELH 58.1 (Spring 1991): 141-165.

Laurens, Penelope. “‘Old Correspondences’: Prosodic Transformations in Elizabeth Bishop.” Elizabeth Bishop and Her Art. Eds. Lloyd Schwartz and Sybil P. Estess. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1983. 75-95.

Lombardi, Marilyn May. The Body and the Song: Elizabeth Bishop’s Poetics. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1995.

McCabe, Susan. Elizabeth Bishop: Her Poetics of Loss. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1994.

McClatchy, J.D. White Paper: On Contemporary American Poetry. New York: Columbia UP, 1989.

Mariani, Andrea. “Orbits of Power: Rings in James Merrill’s Poetry.” Exchanging Clothes:

Habits of Being 2. Eds. Cristina Giorcelli and Paula Rabinowitz. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2012. 58-77.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy vol 1 [1867]. Trans. Ben Fowkes. New York: Vintage, 1977.

Merrill, James. Collected Poems. Eds. J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser. New York: Knopf, 2001.

Millier, Brett Candlish. “Elusive Mastery: The Drafts of Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘One Art.’” New England Review 13.2 (Winter 1990): 121-129.

Muller, John P. and William J. Richardson, Eds. The Purloined Poe: Lacan, Derrida, and Psychoanalytic Reading. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1988.

Poe, E. A. Selections from the Critical Writings. Ed. F. C. Prescott. New York: Gordian Press, 1981.

Schwartz, Lloyd. “Dedications: Lowell’s ‘Skunk Hour’ and Bishop’s ‘The Armadillo.’” Salmagundi 141/142 (2004): 120–124.

Shaw, W. David. “Lyric Displacement in the Victorian Monologue: Naturalizing the Vocative.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 52.3 (December 1997): 302-325.

Shelley, P. B. The Selected Poetry and Prose of Shelley. Ed. Bruce Woodcock. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions, 2002.

Smith, J. Mark. “Apostrophe, or the Lyric Art of Turning Away.” Texas Studies in Language and Literature 49.4 (Winter 2007): 411-437.

Stevens, Wallace. The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens. Corrected ed. Eds. John N. Serio and Chris Beyers. New York: Vintage, 2015.

Vendler, Helen. The Ocean, The Bird, and the Scholar: Essays on Poets and Poetry. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2015.

Waters, William. Poetry’s Touch: On Lyric Address. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2003.

Whitman, Walt. The Portable Walt Whitman. Ed. Mark van Doren. New York: Penguin, 1977.

Yaeger, Patricia, ed. “The New Lyric Studies.” Special issue of PMLA 123.1 (January 2008).

Yeats, W. B. The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Revised 2nd ed. Ed. Richard J. Finneran. New York: Scribner, 1996.

Yenser, Stephen. The Consuming Myth: The Work of James Merrill. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1987.

Zettelmann, Eva. “Apostrophe, Speaker Projection, and Lyric World Building.” Poetics Today 38.1 (February 2017): 189-201.

Notes

1 All quotations for Elizabeth Bishop are taken from The Complete Poems 1927-1979 (Bishop 1983) and those for James Merrill are taken from Collected Poems (Merrill 2001).

2 Lloyd Schwartz corrects the misunderstanding that the poem was written as a response to Robert Lowell, especially his “Skunk Hour.” (Bishop’s dedication was added later.) Schwartz sees “a Cold War metaphor: a dazzling display of airborne fire that mimics missiles of mass destruction dropping on innocent” (Schwartz 121).

3 Compare this to P. B. Shelley’s Sonnet [To a balloon, laden with Knowledge] and its metaphorical “fire”: “Bright ball of flame that through the gloom of even / Silently takest thine etherial way / …Unlike the Fire thou bearest, soon shalt thou / Fade like a meteor in surrounding gloom…” (Shelley 98, ll. 1-2, 5-6).

4 In a 1955 letter to Anny Bauman, Bishop explains, “It is pouring rain which is too bad because it’s a day for fireworks and bonfires, etc.—but very good, really, because there may not be so many forest fires and accidents. Fireballoons are supposed to be illegal but everyone sends them up anyway… They are so pretty—one’s of two minds about them” (qtd. in Costello 76).

5 Various readers have tried to make sense of this inward turn at the end of the poem. “The question for the critic,” Penelope Laurens writes, “…is how Bishop shapes the reader’s response to this beautiful and cruel event. One could say that the poem, by its factual presentation alone, asks us to recognize the chaos these illegal balloons generate. Yet, until the final stanza, there is little to indicate that Bishop’s involvement in the scene is anything more than an aesthetic one” (Laurens 77). We are left with more questions than answers, as the poet “hold[s] the poem back from any easily paraphrasable meaning [in order] to give it moral resonance” (77). Bonnie Costello hears “a strong moral voice break[ing] in to oppose the stance of transcendence and aesthetic mastery”; in its place, Bishop “dramatizes this aesthetic distance and the inevitable return to the rage of the suffering body” (Costello 75). C.K. Doreski notes how “[i]nvocation and resignation collapse together in an impotent outcry as rage displaces epiphany,” leaving only an angry gesture and grieving voice (Doreski 39).

6 Geoffrey Hartman can ask whether it is optative (expressing a wish) or imperative, voice speaking out or attempting an invocation (Hartman 193; qtd. in Culler 2001, 139).

7 Importantly, for de Man, prosopopoeia gives the face (or a figure) but not the essence of the thing. Ann Keniston writes, “Apostrophe thus persists in address that its speaker knows to be unheard, while demanding that both speaker and reader pretend that this absent other is in fact present and capable of hearing” (Keniston 298).

8 For an alternative reading, one which relishes the paradoxical tension between the literal and rhetorical as they relate to the mythical unity of language, see the “Semiology and Rhetoric” chapter of de Man’s Allegories of Reading.

9 William Waters (Poetry’s Touch) cautions against conflating the nuances among modes of address.

10 See Culler 2014, 94. Because lyric poems presume an address (even if it is to oneself), even the first word (as in Shelley’s “O wild West Wind”) can be seen as a turning away of sorts. Other critics have taken these concerns in new directions: Eva Zettelman (who links apostrophe to possible worlds theory and challenges Culler’s presumption that apostrophe categorically denies to lyric the potential to reposition the reader in a language-induced mimetic scenario), Gavin Hopps (who contests the notion that apostrophe is non-representational by offering a “theologically-grounded reading of apostrophe” [Hopps 224]), and David Shaw (who sees apostrophe as central not only to the lyric but also the vocatives of the dramatic monologue, which depends just as much—if not more—on the discursive speech act and the poet’s rhetorical “words of power” [Shaw 325]).

11 The movement from lyric as a genre to lyric as a reading practice has occupied many of the recent debates regarding the status of lyric. See Jackson and Prins 1999, 521-30; and the special issue on “The New Lyric Studies” (Yaeger 2008).

12 One might be reminded of Karl Marx’s “dancing table” and the mystical character of the topological commodity, but our fetish, for the moment, is tropological. Here is Marx: “A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties…. [A]s soon as [the table] emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will” (Marx 163-64).

13 Culler is quoting Wallace Stevens’s “Botanist on Alp (No. 1),” (Stevens, 143, l. 3).

14 “To apostrophize is to will a state of affairs, to attempt to bring it into being by asking inanimate objects to bend themselves to your desire—as if apostrophe, with all its rhetorical fragility, embodied an atavistic casting of spells on the world…. Apostrophes invoke elements of the universe as potentially responsive forces, which can be asked to act, or refrain from acting, or even to continue behaving as they usually behave” (Culler 2015, 215-6).

15 Does poetry, Sara Guyer asks, “survive as a mouth? Does it survive in our mouths? Does it survive because of our mouths or because it gives us mouths? And if it is a mouth, a mouth that survives, what survives is us, us insofar as in voicing it we are made to speak and to live, to live on in a figure, a figure of address” (Guyer 105).

16 The division between the inside emotion and the outside world is perhaps nowhere more felt (at least in 1962 America) than in Skeeter Davis’s [Mary Frances Penick] popularization of the Arthur Kent and Sylvia Dee song “The End of the World”: “Why does the sun go on shining? / Why does the sea rush to shore? / Don't they know it’s the end of the world? / ’Cause you don't love me anymore….”

17 One might lose oneself for years if one were to take this in a Levinasian or Lacanian direction. Invoking Jacques Lacan, John P. Muller writes, “Whereas the subject has always been ‘spoken’ by the unconscious, the task of the analysand, with the help of the analyst holding the place of the Other, is first to discover itself as a subject, that is, to distinguish itself from its own ego caught up in imaginary intercourse with other egos, and then to discover within itself the difference between being subject of the ‘enunciated’ and the subject of the ‘enunciation’” (Muller 72); see also Muller on Hegel, Lacan, and the “I” (346-55).

18 Apostrophe is, per Val Cunningham, “the fundamental trope of prayer” (Cunningham 392).

19 Herbert: “When he preacheth, he procures attention by all possible art…. [B]y turning often, and making many Apostrophes to God, as, Oh Lord blesse my people, and teach them this point; or, Oh my Master, on whose errand I come, let me hold my peace, and do thou speak thy selfe; for thou art Love, and when thou teachest, all are Scholers. Some such irradiations scatteringly in the Sermon, carry great holiness in them” (Herbert 1905, 224-25).

20 Gavin Hopps writes, “faith has its being and is a wagering in advance of such [truthful, confirmable] conditions, which may or may never arrive, or may paradoxically arrive in never arriving” (Hopps 235).

21 For now, I will defer the deeper discussion to the book from which this article will be drawn. The translated critique begins with Of Grammatology (Derrida 1974).

22 Syrinx is also a dangerous watery build-up in the spinal cord.

23 Merrill’s fascination with the O does not end with the lyric form, but rather extends into his prose and epic poetry. This is not to challenge the special place apostrophe might hold for the lyric, but simply to see how this orbiting grapheme might land on other worlds. We see the “O” occupy a shorthand for the narrator’s older half-brother Orson (or “Orestes”) in Merrill’s The (Diblos) Notebook, a novel about writing a novel, which includes excised words and pages, not to mention an upside-down paragraph, as though he were really capturing the process of writing. The O also takes center stage in Merrill’s epic poem of disembodied voices, The Changing Light at Sandover. At over 550 pages, this poem tells the decades-long (or possibly millennia-long) story of the Ouija conjurings in Merrill and Jackson’s home. (Merrill acted as the transcriber and Jackson as the medium, and they used an overturned teacup as the planchet.) The poem recounts their summoning of real and imagined spirit guides, including Ephraim (a 2000-year old Greek Jew), Mirabell (a bat-angel-peacock), and W. H. Auden, among others. Filled on one hand with grand cosmic visions, and on the other hand with the day-to-day domestic life on Water Street in Connecticut, Sandover mirrors the visual layout of the Ouija board. The first part of Merrill’s trilogy is organized, according to the alphabet as an abcedarian of sorts. One divine force in the epic is symbolized by the “Twin zeroes” or the double O, which becomes a measure of infinity or the source of birth (as in the oo of oogenesis) in the middle of the b00k.

24 “Time will say nothing but I told you so” (314, l. 1), Auden’s villanelle boasts, as if teasing us with both knowledge and decay.

25 Alex Bellos writes, in a book that has nothing to do with Merrill but with a title he would have enjoyed: “From zephyr came ‘zero’ but also the Portuguese word chifre, which means [Devil] horns, and the English word ‘cipher,’ meaning code…. Indian philosophy embraced the concept of nothingness just as Indian math embraced the concept of zero. The conceptual leap that led to the invention of zero happened in a culture that accepted the void as the essence of the universe…. The circle, 0, was chosen because it portrays the cyclical movements of the face of heaven. Zero means nothing, and it means eternity” (Bellos 81, 92-3).

26 Bishop’s father died when she was an infant, and her mother was institutionalized. Her longtime lover Lota de Macedo Soares committed suicide about a decade before the publication of Geography III, where the last instantiation of “One Art” finally found its home. Susan McCabe, through a psychoanalytic lens, stresses the autobiographical nature of this poem.

27 There are sixteen known versions, some untitled, others with different titles. One draft connects the lyric speech act with discovery or self-discovery (“I really / want to introduce myself”); another inserts a vocal act of resignation (“oh no”) in the final lines (See Millier).

28 Diehl and Mutlu Blasing stress the connection between life and art. Blasing writes, “the art of writing and the art of losing are one, and the requirements of the form serve to render loss certain from the start” (Blasing 111-112). Unlike most other critics, Doreski stresses the mastery, writing, “This encapsulated lesson is for the master alone; unlike the free, gestural ‘And look!’ designed to deflect attention from the self, the parenthetical injunction maps a course for only one” (15). Anne Colwell considers the contrary impulses. “In the earlier drafts of this stanza,” she writes, “Bishop struggled with the desire to say and unsay, to say two things at once, both admitting to the truth of the argument that the villanelle has established and admitting to the evasion of the truth that the tone has insisted on” (Colwell 178).

29 Colwell writes, “This duality that Bishop works so hard to achieve in draft after draft (there are seventeen drafts of ‘One Art’ in Vassar’s manuscript collection) she finally finds in one word, ‘shan’t.’ This word, with its overformal stiffness, its anachronistic sound, its school-marmish precision, says both ‘I’m lying’ and ‘I’m not lying’” (178). “The whole stanza is in danger of breaking apart, and breaking down,” J.D. McClatchy writes, adding that “[i]n this last line the poet’s voice literally cracks. The villanelle – that strictest and most intractable of verse forms – can barely control the grief, yet helps the poet keep her balance. …” (McClatchy 145). Then, “when ‘disaster’ finally comes it sounds with a shocking finality” (145).

30 Lombardi writes, “the difficulty and restraint associated with breathing and speaking in the poem suggests the ongoing constraints the poet labors under as a woman and a lesbian bound to leading a life of surface conformity and concealed depths” (34).

31 Given the tonal echoes throughout and the almost gradual changes in voice, one might also be reminded of another 12-part circle: the chromatic scale.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : David Ben-Merre

David Ben-Merre is an associate professor in the Department of English at SUNY Buffalo State. His book Figures of Time looks at how nuances of poetic form alter how we have come to understand cultural aspects of temporality. His manuscript on the pedagogical guises of Ezra Pound (co-written with Robert Scholes) is forthcoming with SUNY Press. Currently, he is working on two manuscripts: the first, from which this article is drawn, is on poetic apostrophe, and the second on the value of literary misreading. Selected publications include work on Lord Byron, W.B. Yeats, James Joyce and Albert Einstein, World War I poetry, Charles Dickens, Carly Simon, Giorgio Agamben, James Merrill, Martin Amis, Franz Kafka, J.L. Borges, E.A. Poe, Hilda Doolittle, and the early years of Poetry Magazine. In addition to serving on the Board of Directors for The American Mock Trial Association, he enjoys the light recreation of crossword construction.